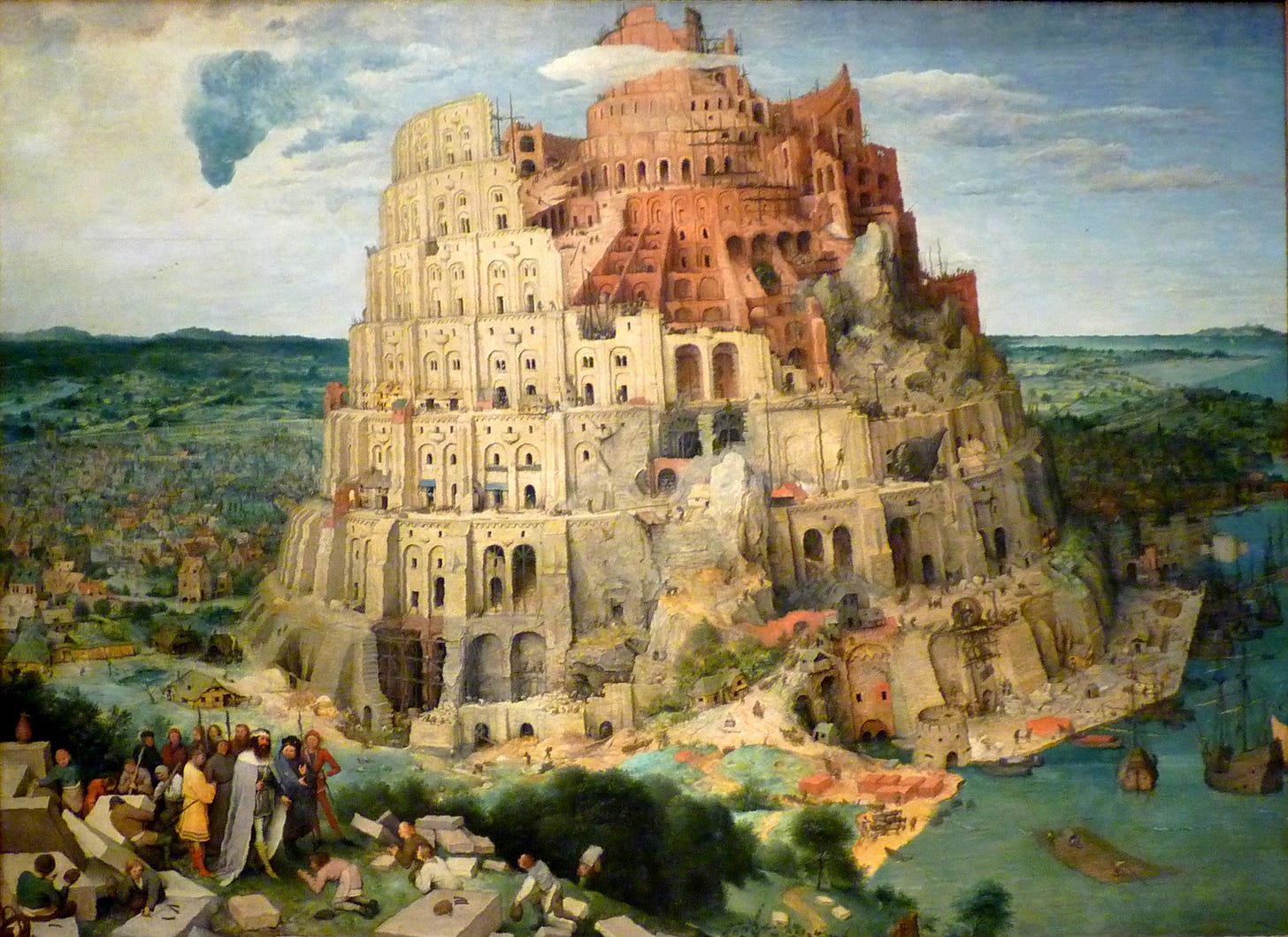

Imagine, if you will, a civilization lost to time organized entirely by its desire for intimacy with God Most High: intimacy both spiritual and proximal. Within an Ancient Near Eastern cosmology, this civilization could only satisfy its longing by erecting a great tower to join the flat earth to the vault of heaven. Such an undertaking would require the labor of many generations: united through oceans of time by a common purpose. That purpose would be always in view, for to exist, the tower would also have to be a city, one whose every stone witnessed to the telos of its people. This city would have to be self-sufficient: for instance, capturing rain in reservoirs to water its gardens and orchards. The form of every material object and process in the city would be determined by its vertical horizon.

Ted Chiang’s short story “Tower of Babylon” begins when this civilization has finally reached the vault of heaven. Hillalum, the protagonist, is a miner tasked with penetrating the granitic vault. It takes him four months to travel from the base to the city’s upper reaches. When at last the vault is pierced, the “waters above” gush forth, and the tunnel is sealed behind Hillalum to prevent the city from being flooded. He has no choice but to swim upward. When he breaches the surface, expecting to find himself in heaven, he discovers he is swimming in the “waters below” just outside the city. The world, he realizes, was like a seal cylinder that was rolled atop wet clay tablets to imprint an image. The figures that appeared as borders on the tablet were, on the cylinder, side by side. “Men imagined heaven and earth as being at the ends of a tablet, with sky and stars stretched between; yet the world was wrapped around in some fantastic way so that heaven and earth touched.” Hillalum marvels at God’s creative wisdom:

It was clear now why Yahweh had not struck down the tower, had not punished men for wishing to reach beyond the bounds set for them: for the longest journey would merely return them to the place whence they’d come. Centuries of their labor would not reveal to them any more of Creation than they already knew. Yet through their endeavor, men would glimpse the unimaginable artistry of Yahweh’s work, in seeing how ingeniously the world had been constructed. By this construction, Yahweh’s work was indicated, and Yahweh’s work was concealed.

I was reminded of Chiang’s parable as I listened to Paul Kingsnorth deliver his First Things Erasmus Lecture, “Against Christian Civilization.” He argues that civilization as such is a consequence of the Fall: “Ever since we were expelled from this garden, it seems, we have been building great towers to the sky, trying, if subconsciously, to return to our true home. But always our towers are brought down, and our tribes are scattered.”

His view is akin to that of René Girard, who held that all archaic culture was birthed in violence because hominization—the process by which our evolutionary precursors became human—itself culminated in the first sacrifice, an event that restored difference to a community on the brink of self-extinction amidst the violent undifferentiation of mimetic crisis. For Girard, civilization was made possible by, and premised upon, the social technology of the scapegoat mechanism. While Girard’s critique of civilization is bleaker and more comprehensive than Kingsnorth’s, it allows for the possibility that a civilization might become genuinely Christian—if only its people would renounce violent reciprocity. It thus offers an illuminating foil to Kingsnorth’s essay, at a time when many minds, especially in America, have fixed on the the raising of towers in the form of the renewal of western civilization. Kingsnorth’s argument is simple: civilization-building is ineluctably idolatrous and antithetical to the Edenic communion God made man to enjoy; therefore, “Christian civilization” is a contradiction in terms. Civilization cannot be baptized. It can only replace Christ with an idol. All towers are Towers of Babel.

Christianity, says Kingsnorth, “is founded upon a set of values inimical to those of our modern, expansionist, acquisitive, growth-obsessed, and apparently ‘masculine’ civilization.” He catalogues some of Christ’s most startling statements, drawn especially from the Sermon on the Mount (for example, Matt. 5:39: “Resist not evil”), and concludes, “Every single one of these teachings, were we to follow them, would make the building of a civilization impossible.”

The teachings of Jesus are radical, in both their rhetoric and politics. Not merely radical—impossible. And so we twist his words, says Kingsnorth. “Oh, yes, I know he said that, we tell ourselves, but he really meant this.” Endless qualifications can be made here, many of them valid. But even a faithfully-nuanced reading of Jesus’s teachings leaves us unsettled, our ears itching for excuses to remarry, to indulge the lust of our eyes, to be more generous to our pleasures than to the poor, to experience our anger always as righteous.

Kingsnorth is right to admonish us. But his criticism applies also to those who take Jesus’s teachings at face value as discrete propositions. An apt example is the way contemporary Anabaptists make the Sermon on the Mount into a “set of values” against which to measure the rest of Scripture. Much more than a set of teachings, the Sermon is a rhetorical performance in which Jesus enacts an authority greater than Moses’s, so great as to be coequal with the Father as Lord of the Day of Judgment. The Sermon is a provocation that both ratifies and upends the Law by revealing its source. Its flourishes of hyperbole (“If your right eye causes you to sin, tear it out and throw it away”) underscore the need for expansive contextual reading. The Sermon’s teachings are irreducible to propositions. They are necessarily polysemous, finding their meanings in the whole of Christ’s life, even as it is lived in and through his church.

This is why, despite some implausibly biblicist readings of certain of Christ’s utterances, Kingsnorth’s lecture, in its total impact, is faithful to the spirit of Jesus’s teachings. Jesus was a stumbling block, a “rock of offense” counter-signaling the Jewish and Roman world. His church has a duty to continue his confounding provocation; sometimes, though, she requires her own confounding from within. In my view, Kingsnorth’s essay operates as such a prophetic counter-sign calling the church back to her native intransigence.

We should heed the exhortation. American Christians are entering a period in which much civilization-building is both necessary and achievable. The temptation for activist-minded believers to fall into idolatry is serious, and we must take care to distinguish between faithfully building for the common good and placing our faith in the things we build instead of in Christ. Culture and civilization are worthy of our restorative efforts, but they are unfit for worship.

Kingsnorth’s dismissal of cities and civilization as intrinsically fallen is too extreme. Civilization is simply the scaled sociality of humans made in the image of the Maker; as such, it would still have existed absent the Fall (though in what form we can only speculate). It is true that in Genesis the first city is founded by the first murderer—Cain, who, as Kingsnorth might wish to note, was a grower of crops (there can be no civilization without agriculture). This detail is consonant with René Girard’s contention that archaic cultures coalesced around acts of collective violence. “Because humans imitate one another,” writes Girard, “they have had to find a means of dealing with contagious similarity, which could lead to the pure and simple disappearance of their society. The mechanism by which they have done that is sacrifice, which reintroduces difference into a situation in which everyone has come to resemble everyone else.” The recapitulation of that spontaneous sacrifice in the orchestrated sacrifices of religious ritual forms the basis of culture; all historical civilizations have their genesis in sacred violence. If we have in view only the cities and civilizations of history, Kingsnorth is correct: they are shot through with idolatry.

However, to observe that the material substrate bears the form of the city imperfectly (or even perversely) does not negate the inherent goodness of the form. Because the line of good and evil runs through every human heart, it also runs through every merely human city. In contrast, the Apocalypse of St. John envisions the heavenly city—the perfectly incarnated form of maximally scaled divine-human sociality—descending on a recreated earth. The New Jerusalem contains the Tree of Life, suggesting Eden itself was always destined to become a city.

St. Augustine notes in City of God that the earthly city “is itself mastered by the lust for mastery.” He was writing at a time when western civilization was becoming recognizably western; even earthly cities inhabited and administered by Christians were ruled by the libido dominandi. And yet the form of civilizational self-critique he modeled would itself become a characteristic practice of Christendom.

Even at its worst, western civilization has been substantively different from other civilizations. Britain was far from a just society when it began to colonize the Indian subcontinent in the eighteenth century; but it did not practice sati (widow burning). Nor was Spain especially virtuous when it conquered Mexico in the early-sixteenth century; but, unlike the Aztecs and Mayans, it did not sacrifice untold thousands of innocents to sustain the cosmos. All civilizations are fallen, violent, and unjust. But only western civilization is premised on the rejection of sacrificial economy. This is solely because it was leavened by the gospel.

In his death, Christ demonstrated that victims of scapegoating are innocent, thereby exposing the mythical lie at the heart of fallen civilization. His resurrection inaugurated the new means of solidarity: his body. A civilization is “Christian” to the extent that its cultural forms and institutions practice that rejection of the victimage mechanism, of the violent sacred, and ground their solidarity in the church. The abolition of sacrifice amounts to practicing what Girard called “political atheism,” the refusal to believe in the state’s divinity.

“The protective system of scapegoats is finally destroyed by the Crucifixion narratives as they reveal Jesus’s innocence and, little by little, that of all analogous victims,” writes Girard. “The process of education away from violent sacrifice thus got underway, but it moved very slowly, making advances that were almost always unconscious.”

Western civilization first became distinctively western—that is, moved decisively in the direction of ontological peace by de-sacrificing—under Constantine Augustus. As Peter Leithart explains, “By eliminating the civic sacrifice that founded Rome and protecting and promoting the Eucharistic civitas, Constantine was, in effect if not intent, acknowledging the church’s superiority as a community of justice and peace. He was acknowledging, whether he recognized it fully or not, that the church was the model that he and all other emperors should strive to imitate.”

Christians in America (and elsewhere) have a duty to build civilization in order to fulfill Christ’s command to love our neighbors as ourselves. We must face that duty with the knowledge that the church is our true polity, our true home, and Christ the true measure of building well. To build a Christian civilization first of all requires the church be the church. It also requires cultivating a sanctified imagination capable of envisioning a world without death—not only the death of victims, but death as the horizon of life.

It is undeniable that the universal goods of Christian faith are mediated through the particular; affection for one’s earthly home—including one’s people, one’s nation—is natural and good. But that affection and the experience of home are conditioned within a fallen world where human death is a reality.

Phenomenologically, death is the stable point of reference that allows a given location to become a specific, meaning-laden “place” within our experience. This is most especially true of the place one calls home. As Coulange demonstrates in The Ancient City, the earliest “homes” were also burial sites. The interred bodies of one’s forebears are the precondition of both the home and the city—and, indeed, of all human culture and civilization. All human language, and thus all human thought, takes the marked grave as its primordial referent, for in the grave signifier and signified are one. Consciousness of death is inextricable from our phenomenology, and thus from our labors in building. As the cities of Ancient Egypt vividly illustrate, the City of Man is a necropolis.

The City of God is deathless. And yet it is the standard toward which the Christian must build if he is to build as a Christian for his neighbor’s good. We find ourselves in a situation similar to that of the inhabitants of Ted Chiang’s “Tower of Babylon,” compelled to pursue a beautiful yet impossible end. The key difference is that we know in advance that the goal cannot be achieved by human means. Girard understood that Christ’s revelation of the mythical lie removed “humanity’s sacrificial crutches,” leaving us either to renounce violence in imitation of Christ or to perish in a conflagration of mimetic crises that can no longer be resolved by sacrifice. We continue to choose the latter. “Christianity is the only religion that has foreseen its own failure,” writes Girard. “This prescience is known as the apocalypse.”

It is metaphysically impossible to build the City of Man into the City of God; for beings cannot transform themselves into Being. This is liberating. Just as beings participate in Being, the cities of men can and should be built so as to participate in the beauty and goodness of the City of God. We might think of the artist who builds immense sand sculptures on the beach. The inevitability of the tide does not diminish the sculptures’ beauty but enhances it. We are invited to build civilization with a similar lightness.

In his final book, Girard exhorts us to “battle to the end,” but he doesn’t specify what this entails. Likewise, Kingsnorth offers little in the way of practical guidance—indeed, he revels in the “uselessness” of Christianity. And yet one of his themes is quite germane for developing a faithful disposition toward building. He writes,

The monks built the West, just as surely as the soldiers did, and they built the more enduring part. “Christian civilisation,” wrote the liturgical artist Hilary White recently, “is the secondary fruit of Christian mysticism.” This is the essential point. Prayer is the heart of the matter. Christ is the heart of the matter. Without the heart, there is no body. Trying to work backward—to build a body, as it were, with no heart—is an impossibility.

In the church, some are called to the contemplative life, many others to the active. Neither can exist without the other. The prayers of the hermit waging war in the heavenly realms spiritually nourishes and protects the brothers who tend to the nourishment and protection of his physical body. Something analogous must take place in our civilization building: Christians active in civic life have a duty to ensure the church is free to do its spiritual work. Among other things, this means securing the material conditions necessary for contemplation—above all, sufficient stillness.

Only true contemplation can overcome the ersatz mysticism of the mob, in which the individual loses himself in an ecstasy of violent undifferentiation. True contemplation requires self-giving, the sacrifice of one’s difference for the sake of oneness with God, a finite kenosis that participates in the infinite kenosis of God’s creative act, whereas the undifferentiation experienced by the mob-man is rooted in self-centeredness. After all, it is the self-centered pursuit of desire that creates the mimetic crisis to begin with. In Deceit, Desire and the Novel, Girard stresses that the novelist must overcome his own self-centeredness in order to see the currents of mimetic influence that govern the relationship of Self to Other; without such self-overcoming, the novelist will never produce a masterpiece. Writes Girard:

To triumph over self-centeredness is to get away from oneself and make contact with others but in another sense it also implies a greater intimacy with oneself and a withdrawal from others. A self-centered person thinks he is choosing himself but in fact he shuts himself out as much as others. Victory over self-centeredness allows us to probe deeply into the Self and at the same time yields a better knowledge of Others. At a certain depth there is no difference between our own secret and the secret of Others. Everything is revealed to the novelist when he penetrates this Self, a truer Self than that which each of us displays. This Self imitates constantly, on its knees before the mediator.

Contemplation habituates us to self-giving, preparing us to sacrifice our desires for the sake of defusing negative reciprocity, thereby halting the escalation to extremes. The peace of contemplation opens space for genuine self-knowledge, and thus for genuine creation—from novels to architectural marvels—creation ordered to the City of God. Conversely, the noise, the divertissements that make contemplation difficult or impossible ensure our creations are decadent, ordered to an entirely different city.

Opposing the City of God to the City of Man, absent their full cosmic context, can produce a false binary. In reality, the City of Man is the contested territory in a war between the New Jerusalem and the Infernal City, between the City of Music and Silence and the City of Noise. Hence the elder demon’s paean to cacophony in C. S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters:

Music and silence—how I detest them both! How thankful we should be that ever since our Father entered Hell. . .no square inch of infernal space and no moment of infernal time has been surrendered to either of those abominable forces, but all has been occupied by Noise—Noise, the grand dynamism, the audible expression of all that is exultant, ruthless, and virile—Noise which alone defends us from silly qualms, despairing scruples, and impossible desires. We will make the whole universe a noise in the end.

The fall of Babylon the Great in The Apocalypse of St. John is the fall of a city consumed by noise. The entropy of mimetic conflagration is unbearably loud—an undifferentiated lunatic howling—until it’s not. The Apocalypse depicts a Babylon burned to silence. If the cities of men refuse the peaceful silences of heaven, they will suffer the violence of heat death, the silence of judgment.

For all its virtues, western civilization has become a civilization of noise. Almost every feature of daily life is designed to deny us contemplation. Kingsnorth is right to yearn for a new flowering of Christian mysticism. But for that to happen, Christians must build, and build for silence.

*This essay is from the essay collection, Be Not Conformed: René Girard at the Intersection of Athens, Jerusalem and Silicon Valley, edited by Luke Burgis and forthcoming from Catholic University of America Press February 2026.

On Western Civilization being built on the idea of 'no sacrifice'. I'd argue that the West's implicit racism (which is now becoming clear for all to see) is a form of sacrifice: slavery, white supremacy and now ICE and Gaza. But maybe you have a point here. Since the overt cultural projection didn't have this framework for sacrifice, the primal violent forces expressed itself in creating an entire consciousness around racism - sacrificing brown and black people (not really murdering them at the altar) but actively participating in institutional and foreign policies designed to oppress and ensure brown and black bodies die a slow death).