Violent Conflict, the Struggle for Identity, and the Contagion of Mimetic Desire in the Prison Environment

An essay by Carlos Garcia, inmate of Muskegon Correctional Facility.

Editor’s note: This summer I was invited by the Hope-Western Prison Education Program—which provides a Christian liberal arts education to long-term incarcerated men at the Muskegon Correctional Facility—to attend the convocation for the start of their new academic year.

I learned that over the past three years, my book Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life has been used in a first-year seminar for incarcerated students. One of those students, Carlos Garcia, became especially passionate about applying René Girard’s mimetic theory to prison reform. He went on to read every work by Girard he could get his hands on, and began sharing the ideas with other inmates who believe that positive mimesis is possible.

Mr. Garcia published an essay he wrote from prison in Contagion, a journal dedicated to Girard’s thought. Special thanks to Michigan State University Press, which publishes Contagion, for allowing us to share an amended version here.

On August 26, 2025, I visited the prison and had lunch with Mr. Garcia and several other students. It was a joy to be with them. I left convinced that Girard’s insights have a real role to play in rehabilitation and reconciliation. I trust this essay offers a glimpse of that possibility.

—Luke Burgis

My name is Carlos Garcia. I am 56 years old and a junior class member of the Hope College-Western Theological Seminary Prison Education Program (HWPEP). I have lived my entire life in the state of Michigan. Unfortunately, more than forty of those years have been spent in juvenile detention centers, county jails, rehabilitation centers, reformatories, and prisons. I have been accused, tried, and convicted legitimately, and wrongfully, for just about every crime less than murder. Needless to say, I know a thing or two about violence. As a result, I have embarked on a journey to understand and make use of those things I have learned, in the field of mimetic desire, to challenge the current system of prison politics. This essay attempts to address and answer the question, “What role does mimetic desire play in the prison environment, and what effect might it have on the violence therein?”

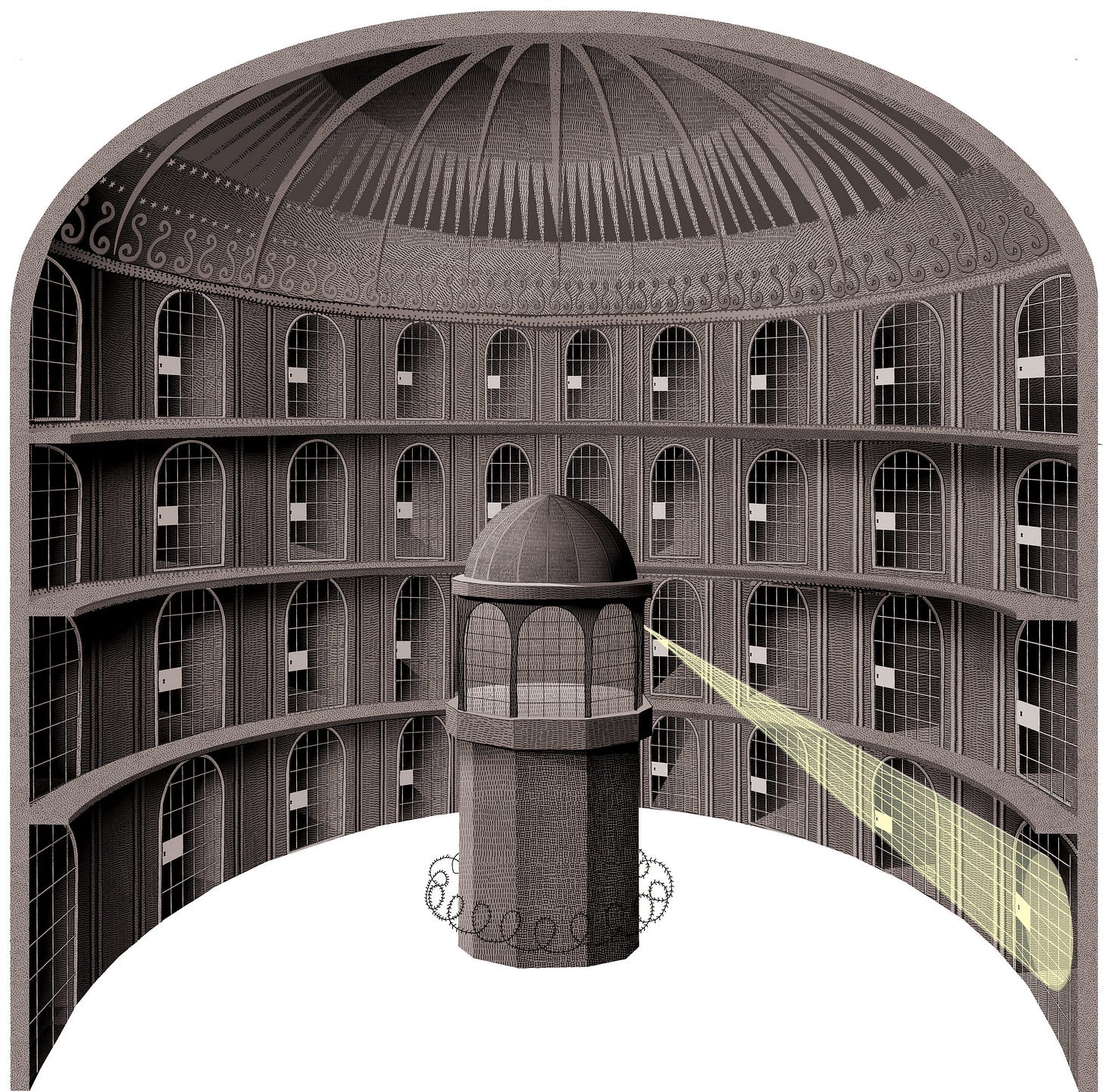

Here, inside the Muskegon Correctional Facility, there is only one television in the day room, and there are 238 inmates in the housing unit, and one remote. Everyone is forced to wear the same kind of clothing, eat the same kind of foods, use the same showers and toilets and the same spaces where they are forced to sleep. Everybody is reaching for the same objects at the same time, caught in a mimetic struggle, and often becoming, at least from this writer’s experience, the very thing I hate: a savage.

It is, I argue, this environment of sameness and the disintegration of differences—not the differences—that ultimately leads to mimetic desire, competition, and rivalry. Winning the rivalry then replaces the initial desire for the material, intellectual, or social object as the desired goal.

Mimesis, mimetic desire, and mimetic theory are rooted in the idea of imitation. Mimesis, in and of itself, is nothing new. It is defined as “imitation or mimicry.” In the context of this essay, however, I address mimetic desire more specifically, as it has been theorized by the French professor of history and literature René Girard. Luke Burgis, the author of Wanting: Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life, defines mimesis as “A sophisticated form of imitation that in adults is usually hidden. In mimetic theory, mimesis has a negative connotation because it usually leads to rivalry and conflict.” Mimetic desire is defined as “Desire generated and formed through the imitation of what someone else has already desired.” This means that what we want or desire is what the other—someone we might consider to be a model or mediator—wants, or desires, not necessarily because of the intrinsic value of the object, but because of the value we perceive the other’s desire has placed on it. Mimetic desire is at the center of most conflicts, and the struggle for identity (i.e., autonomy) that I believe makes the prison environment volatile.

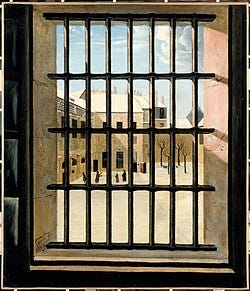

We, as a species, struggle to find our place in the world. Each of us is trying to create our own identities: individually, culturally, collectively, even nationally. In very few places is the struggle more real, or its potentially violent consequences more severe, than in the prison environment. The identities of most inmates have been lost or stripped from them. Their names have been replaced with numbers. Their pasts, and who they believed themselves to be, have been erased. What is left are memories, which for some will become like dreams that they never actually lived. The question for this writer is, “Who, or what, will these men and women become?” Better yet, “Who will I become?”

Jenna Geick’s essay “The Stranger, the Crowd, and the Lynching: Using Mimetic Theory to Explore Episodes of Human Violence,” tells us “All humans experience a lack of being: humans feel insufficient, inadequate, and impoverished.” What I am suggesting is that the stripping of one’s being upon incarceration pushes men and women into making every effort possible to regain some sense of it (i.e., identity), no matter how great or small.

This sense of being is seen as held by other individuals or groups at the top of the prison hierarchy. They become models to those who, themselves, lack being. This, I argue, is the same as lacking power. It is the power that now seems desirable. People believe that if they seize power, or at least imitate those with power, it may give them a sense of identity.

For understanding the purpose of power and conflict in a prison setting, Edgar, O’Donnell, and Martin state, “We can distinguish four ways that power can be exercised:”

Willpower (i.e., nerve).

Political power (yes, there are politics to prison living and surviving, which includes networks and jail wisdom).

Economic power (wealth as trader or debtor).

Official power (prison jobs, privileges, and the ability to move around the facility with relative freedom).

However, what most people (speaking from a prisoner’s perspective) consider to be the ultimate sign of power is the fear that any one individual or group might instill in the rest of the population. This is the kind of power that many seek to possess, that is most contagious, and often the cause of brutal conflicts. It subsumes within it all four of the examples just provided. Often this kind of power is exercised and hidden behind what many have mistakenly identified with respect, and is associated with one’s identity. One might ask, “Is power truly the object of desire?”

It might be easy to assume that the scarce resources, close quarters, or even the disparities between racial groups fuel the most extreme violent behaviors behind prison walls. Peter Wallensteen has proposed that a complete definition of a conflict, as a social situation, is one “in which a minimum of two actors (parties) strive to acquire at the same moment in time an available set of scarce resources.” But Roberto Farneti argues that “the pull of the object is not critical to the outcome.” Rather, “it is the discord itself that prompts the stakes.”

There are differences between prisoners—cultural, religious, socioeconomic—yet differences are not the reason for prison conflict: they are simply the excuse. Girard argues, “Order, peace, and fecundity depend on cultural distinctions” and “it is the loss of them that gives birth to fierce rivalries and sets members of the same family, or social group at one another’s throats.”

With all differences removed, members of the inmate population have been turned into mirrored images of one another. They are essentially the same in every way. Those in charge of implementing, and maintaining, a prison environment of sameness may even believe that they have created safer prisons because of it. In fact, they have created ticking time bombs, always teetering on the verge of all-out war.

There was a time when the inmate population was able to purchase and wear clothing from outside vendors. Some literally wore mink coats, alligator-skin shoes, and gold chains that looked like tow chains. As a result, there was a high rate of violent robberies, stabbings, and even murders to possess those things that some could never have purchased on their own. The cure, so it was thought, was to make everyone the same. But this only created a new level of violence and new objects of desire. As argued earlier, it is not our differences that create conflict. It is in the lack, or disintegration, of those differences that the seeds of conflict are sowed. I believe, while also being mindful of the security needs that each prison must concern itself with, that we can maintain and promote those differences in a way that encourages positive behavior, thereby changing the prison culture itself.

What if there were another way? What if we could create prisons that were less violent and actually functioned, while at the same time serving society’s need for justice? It is my belief that if we would change our mindsets from that of correction and punishment toward that of recognition, rehabilitation, and change, we might then be better able to protect those behind prison walls as well as those outside of them. But how might such a thing be possible, and what might that look like?

First, I would propose that the best approach is the same approach that created the need for such institutions to begin with: a mimetic approach. This could be done by creating an environment where fear is no longer the driving force that pushes men and women toward desiring the kind of power that dominates, but rather an environment that propels them forward toward a stronger sense of self without fear, and where there exists an environment with a greater sense of positive mimetic reciprocity with others. While this may seem a monumental task, it is not impossible.

Second, I would suggest a restoration of what was taken from men and women upon entering the penal system: their individual identities. This could be simply done by identifying individuals on their identification cards as Sir, Mr., Ma’am, Mrs., or Miss, rather than Offender Gar*** #185***. It might also be done in the way men and women are verbally addressed by staff. There is a kind of dignity that comes with being called by name or title. In this simple way, restoration and the creation of a new identity, real or imagined, begin to take form. These men and women are suddenly recognized as having a sense of worth and place in their community, beginning in the prison community. These types of things are personal and foster personal responses.

As an example of change, with mimetic implications already visible, I would like to direct your attention to the Hope College–Western Theological Seminary Prison Education Program, which was established as a collaboration of the two institutions, and at the approval of Michigan Department of Corrections Director Heidi Washington and the facility warden and administrators. This is a Bachelor of Arts degree program and is currently in its fourth year of operation at the Muskegon Correctional Facility. The program was created with the hope of changing not just the lives of the men who have taken the initiative to participate in it, but also the very culture of the prison environment. In so doing, what they have done, perhaps without realization, is to create a new mindset within the men involved. They have created a sense of connectedness between them and society beyond the fences to which they once felt no connection at all.

On the first day of class, each of the students was instructed to introduce himself. Some gave only their first names. Others gave their first and last names. At least one, possibly two, gave the names that they were most affiliated with on the prison yard and in the streets. This was not acceptable to the professor. We were asked to reintroduce ourselves. This time, while standing, we gave our first and last names. Many of the men I had not known by their full names.

There was a visible apprehension among the men. I wondered if this was because they had forgotten that they had once been identified by those names, or if they somehow felt that their given names would diminish the identities they had assumed in their street names: names like Sneak, Shooter, G-Money.

The professor, in turn, then addressed the students as Mr., Sir, Gentlemen, Scholar, and Colleague. Initially, these titles seemed odd and made many uncomfortable. However, within a few short weeks, the students began addressing themselves as the same. It was not just a classroom phenomenon; these exchanges continued out onto the prison yard, where one’s image and call sign (i.e., street name and therefore identity) cannot afford to be compromised. These men—most of them with violent histories, and still loosely affiliated with the various street and prison gangs that they had aligned and identified themselves with—now walked across a regularly violent prison yard with book bags slung over their shoulders. With them, they carried the shaping of a new identity. This was something the entire body of inmates began to take notice of. This was also something the students themselves began to notice. Yet they were unaware of the mimetic implications they were introducing into the prison culture.

There existed a new glow to these men. It was the glow of a growing humility. Those still trapped in the pull of mimetic desire struggled to find their identities in the negative other and laughed at the first cohort of students. Others questioned the benefit of their efforts. “What good is a degree going to do for you in prison? You are serving a life sentence, why waste your time?” Some, that is, those with less threatening histories and prison identities, were openly called frauds, puppets of the system, and a few other derogatory names. Others spoke in whispers, worried that if Shooter or G-Money heard them, there might be undesired consequences.

There was, however, another change taking place at the same time. This one did not involve the student body. This one was taking place in the community of onlookers, and it included those who had initially mocked and teased this group of scholars. The mode of questions had begun to change. They became, “What are you guys studying? Do you mind if we sit in with you? How do I become a part of the program? How do I get one of those book bags?” The initial desire was not that of an academic nature, but rather, it was for the book bag. This was a new item on the yard. It became a valued item for each student who had one. And the only way to acquire one was to become a student.

Of course, there were still those who mocked and ridiculed this new breed of prisoner. There were also staff members who seemed bothered by the fact that these men were actually becoming something other than that which they had been before. Yet there were some staff members who also began responding to these men differently as well. The title Mr. began to be spoken out loud by them. They too began to ask about the subjects the students were being taught. Some even engaged them with their own studies. What an amazing thing this was: to be a student of mimetics, and to witness its effects in real time, convinced me that this was the field of study for me.

During Vern Neufeld Redekop’s studies on reconciliation, he noticed: “A mimetic structure of violence is something bigger than any one individual. It can infuse a relational system, putting pressure on those caught up in it to orient themselves towards action meant to harm or disempower the other.”

Redekop proposes that this is the mimetic structure of violence. I am proposing that its mirrored opposition would be the mimetic structure of nonviolence. It, too, is something bigger than one individual. However, as is the case with mimetic violence, it only takes one individual to spark and create a mimetic contagion. It is then the importance that the individual places on the act of violence, or in this case, act of kindness, that determines the level of infusion to which the contagion spreads.

Redekop wondered what it might be that would change or designate another orientation—that is, for an orientation of violence to change to one of nonviolence. His idea was to incorporate “blessings.” Understanding the religious and controversial connotations of this word, he developed an argument supported by the historical origins of the word that would allow him to enter conversations on conflict studies. In fact, he developed a new definition that, in essence, altered the understanding of blessing from its Hebrew origins—that is, from a state of vulnerable receptivity to a place of generous reciprocity. Here, all parties are engaging in reciprocal giving and receiving of joy, confidence, self-esteem, peace, dignity, and respect.

It is within this space, a space of generous reciprocity, that the HWPEP program has stepped. I am a grateful recipient of this, and fully aware of the mimetic implications, changes, and opportunities that education can create in the lives of those who fully engage the program.

Identifying these men as individuals, recognizing, respecting, and nurturing their individual differences, has removed them from a position of sameness that had, for years, trapped them in a state of perpetual conflict within themselves and those around them. Yet this is the condition that was created by the very system tasked with the responsibility of rehabilitating them.

This, Farneti argues, is “the peak of mimetic conflict, when the story of reciprocal imitation has escalated to the point that the very [differences have] been erased and the rivals stand in front of each other matching images of violence.”

The prison environment, by its very nature of sameness, then, stands at the precipice of what could be a mimetic killing field. This is the thing we must avoid if we ever hope to change the shape of our mimetically violent natures. We must create an environment that respects the differences that naturally exist in one another.

Most of the men and women that our society is all too eager to incarcerate as a means of safeguarding our communities will one day be released. The question now is, will they be released into the same societies, welcomed by the same models that led them toward, and down, the path of their own damnation to begin with? Do these communities even know they played a part? Or will our prisons and communities, in failing to recognize the power of mimetics, continue to create systems of sameness that foster rivalry and conflict?

Who will choose from among us those deemed to be most undesirable? Who will be the most expendable? The worthiest of our wrath?

Carlos, thank you for your commitment to improving the lives of prisoners and prisons! You are doing great work in your commitment to the cause! May God continue to bless your mission and all the people you and the Hope program touch!

This is powerful. Thank you sir.