In 1917, the Russian literary critic Viktor Shklovsky wrote the essay “Art as Device,” in which he suggested that much of human experience becomes invisible by habit. Habit deadens the world and makes us effectively blind. But the purpose of art, he wrote, is to “defamiliarize” experience, in order to illuminate those aspects which have become invisible; to bring to life that which has died.

This process is illustrated in a passage from the memoir White Out by Cluny Journal contributor Michael Clune (no relation):

Something that’s always new, that’s immune to habit, that never gets old. That’s something worth having. Because habit is what destroys the world. Take a new car and put it in an air-controlled garage. Go look at it every day. After one year all that will remain of the car is a vague outline. Trees, stop-signs, people, and books grow old, crumble and disappear inside our habits. The reason old people don’t mind dying is because by the time you reach eighty, the world has basically disappeared.

And then you discover a little piece of the world that’s immune to habit.

Art is one endeavor that has strived for this habit-immunity. Art is a technology for defeating habit. But there are also other experiences that jolt us into new ways of seeing and being in the world—breaking a bone, encountering a genetically-modified landscape, limiting some of our senses, learning a language. Certain technologies, spiritual practices, and interdisciplinary encounters can also defamiliarize experience.

In daily life, perception becomes streamlined, flattened, and erased—walking up the stairs, turning the bathroom doorknob, endlessly scrolling the parade of fragmented images and texts, all of which are encountered more or less invisibly, and then forgotten. “Automatization,” Shklovsky writes, “eats away at things, at clothes, at furniture…and at our fear of war.”

By restoring vividness to experience—and by exploring rather than explaining—defamiliarization can restore reality itself. But in order to make us “feel objects”—to make “a stone feel stony again”—we have to estrange it, “to lead us to a ‘vision’ of this object rather than mere recognition.” The dominant culture deals in explanations and discourse—but these often fail to affect lasting change at the level of perception, unwilling to linger in the essential strangeness and surprise of life. In the face of the soul-numbing scroll, encounters that enlarge perception can make life itself again feel new.

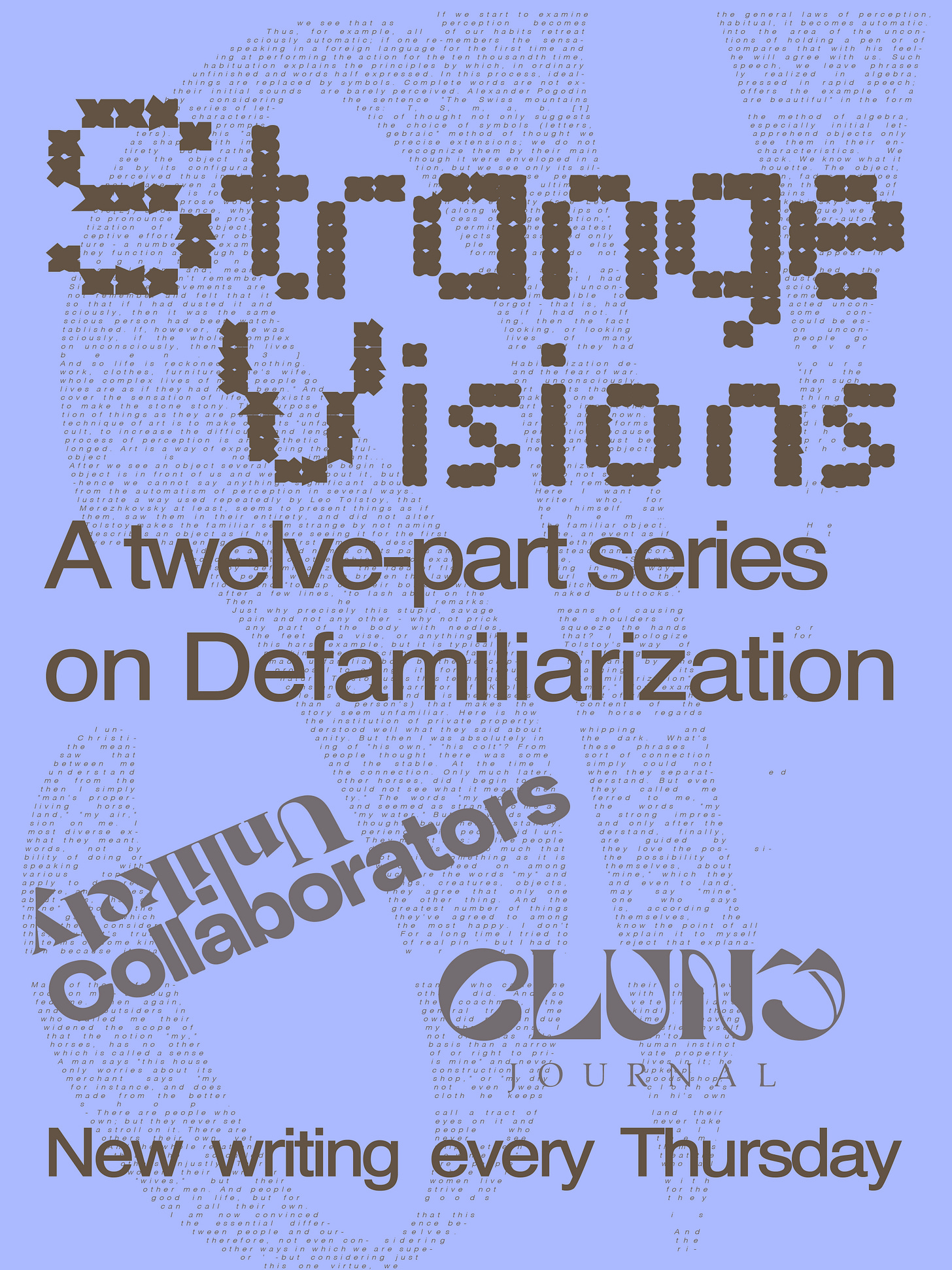

In this new year, Cluny Journal is partnering with Unlikely Collaborators for a twelve-part series on defamiliarization.

Every Thursday for the next twelve weeks, we will publish pieces by filmmakers, artists, writers, scientists, technologists and others who engage with the theme on a formal and/or conceptual level. We will explore moments when habitual modes of seeing are disrupted; where mere recognition is replaced by strange visions.

Tom McCarthy explores this idea in the novel Remainder