It was the evening after Election Day and I was speed-walking—while sedated— through JFK to catch a plane to San Francisco. Speedwalking while sedated is comically disorienting; I felt like one of those cartoon characters whose bottom half is a spinning wheel while the top half remains motionless.

I was drugged for dull medical reasons. Also, and annoyingly, I wasn’t drugged quite enough. The sedatives scared me—they are the kind with alarmingly well-researched brain-liquifying qualities—and so I’d taken a tiny fraction of the indicated dose. And I still felt like my brain was changing texture! It was worrisome. I’m too old to be incorporating new modes of self-destruction.

The gate was located as far as possible from the security line, at the actual terminus of Terminal 4. By the time I got to the jet bridge I’d walked a mile and my neck was kinked from mishandling the weight of a carry-on bag containing: 13 books, 4 pairs shoes, 3 notepads, 1 laptop, 1 transparent lime-green cardigan, 1 toothbrush, 5 pairs socks, 2 sweaters, 2 shirts, 0 pairs underwear (forgotten), 1 mini container of conditioner but no shampoo (forgotten), and no hairbrush (also forgotten.)

I was last to board. There had been an issue with my ticket. Originally I’d booked my daughter as a “lap infant” on the trip. Later, for various reasons, it seemed better to leave her at home with her father, so I called the airline and explained the situation. They promised to detach (their word) the baby from the ticket. But the detachment didn’t take, so at the airport I found myself answering at every checkpoint the question of why my daughter was missing.

She isn’t missing, I kept saying. It was hopeless: any administrative irregularity that sits at the intersection of “children” and “crossing state lines” is met with impassable suspicion. Not being good at formal logic, I couldn’t find the words to differentiate “missing” from “intentionally and innocently absent.”

Eventually I got through—each successive agent caved out of boredom—and was seated on the plane. Safely, soundly. And my seat was in an emergency exit row, how wonderful! Except— a flight attendant soon came along to explain that I couldn’t sit in the emergency exit row because I had a baby with me. I explained one last time that there was no baby, only me. The flight attendant glanced around—to make sure I wasn’t hiding my child in the seatback pocket?—and retreated with an air of being unconvinced but with better things to do.

As the plane taxied my neighbor rotated 45º in his seat and struck up a chat. He worked in the wine business and had downloaded the new Sally Rooney novel to read but was having trouble getting into it. It wasn’t as easygoing as her earlier books, he said. When I’d had enough of chatting I retrieved a book of my own—a book called The Right to Oblivion— and placed it prominently in my lap, title facing up, at which my neighbor laughed and went his separate mental way. The plane mustered itself into the sky.

The Right to Oblivion had been emitting oppressive static from my bag. The author, Lowry Pressly, is trained in philosophy. An area of personal shame is that I’m a bigot when it comes to contemporary academic philosophy. No matter how important I consider the work as a cultural product, its actual expression often strikes my generalist brain as exhaustingly contingent and mired. This attitude—the defensive crouch—is not a good way to navigate a field! Pressly’s book was the centerpiece of the Make Molly Read Philosophy Again campaign strategy.

It starts with privacy. Pressly argues that the parameters of the privacy discourse have been sinisterly captured by those who would wish to diminish or exploit it, and that we’ve wasted a lot of time quibbling over e.g. surveillance while unwittingly relying on e.g. Mark Zuckerberg’s terms. I’m synopsizing crudely. Pressly’s conception of privacy is both capacious and utilitarian; he fashions it as a tool we might use to preserve the precious condition of oblivion. Oblivion: a holy space of the unknown that is “resistant to articulation and discovery”—a space that is essential to maintain in ourselves and the world if we are to survive with any measure of joy, freedom, depth.

Right around the moment I was wondering whether my consciousness of privacy had been built on a lie, the plane hit turbulence. “Flight attendants take your jump seats,” said the pilot, and there was a subtle shift in cabin pressure as 400 passengers simultaneously tensed their jaws. My neighbor sighed and put away his Kindle; he had just managed to get into the Sally Rooney. Suitcases banged, bathroom doors flapped. My puny sedative had worn off. Turbulence turns a plane into a frightened congregation: there is nothing to do but sit in rows and abide the force of mystery. Mid-air jostling might be the perfect stage for an encounter with Oblivion.

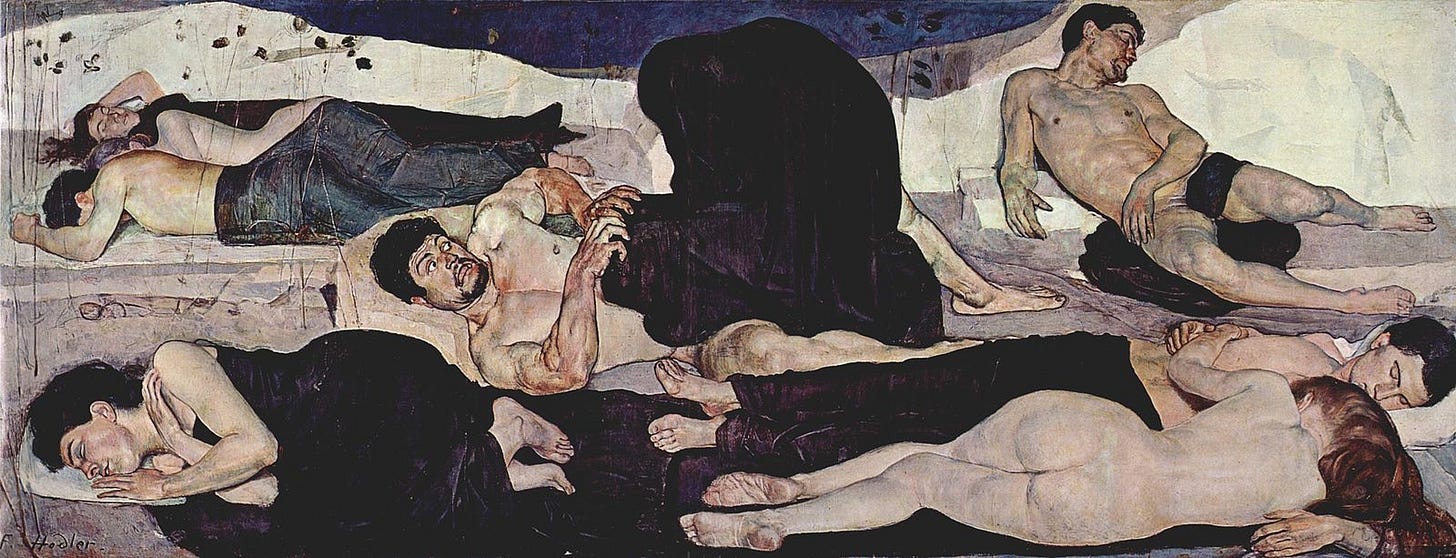

In order to get through it I decided I would flout the standard advice and focus my thoughts on the destination rather than the journey. San Francisco: the place where I’d grown up. San Francisco, a city of microclimates, clinker brick, invasive plants, massage parlors, streets named after milkmen and felons, casual barbarity. A place where it wasn’t uncommon to pass someone splayed on the pavement and find oneself unsure whether the person was alive or dead—a fact that, if you went by Frank Norris, was as true in 1900 as in 2024. And to all this a new epigraph could be added, perhaps: San Francisco, the epicenter of the Great Oblivion Heist of the 20th Century.

Twenty minutes later the jolts petered out. “I make this trip twice a month,” my neighbor said, his face red with irritation. “That shit happens every time over Colorado.” He picked up his Kindle and attempted to re-enter the quiet kitchens and tidy bedrooms of Sally Rooney. I picked up my book with the idea—an idea propelled by decades of reading—that if I couldn’t accomplish the thing under discussion, at least I could learn more about it. The pilot came on to tell us we were through the weather. There was a collective exhalation and stampede-to-the-bathroom. I was glad my daughter hadn’t been present for the turbulence but confident that she would have been fine, yes, absolutely fine.

Guess I'll start reading philosophy now. But won't tell anybody?

Love it!