A Confession by Leo Tolstoy (2/6)

In which Tolstoy grapples with despair, and an unsatisfying search for meaning...

We continue our serialization of Tolstoy’s spiritual autobiography, A Confession. Below is part II of VI. If you haven’t yet, you can read Part I here.

IV

My life came to a standstill. I could breathe, eat, drink, and sleep, and I could not help doing these things; but there was no life, for there were no wishes the fulfillment of which I could consider reasonable. If I desired anything, I knew in advance that whether I satisfied my desire or not, nothing would come of it. Had a fairy come and offered to fulfill my desires I should not have known what to ask.

If in moments of intoxication I felt something which, though not a wish, was a habit left by former wishes, in sober moments I knew this to be a delusion and that there was really nothing to wish for. I could not even wish to know the truth, for I guessed of what it consisted. The truth was that life is meaningless. I had as it were lived, lived, and walked, walked, till I had come to a precipice and saw clearly that there was nothing ahead of me but destruction.

It was impossible to stop, impossible to go back, and impossible to close my eyes or avoid seeing that there was nothing ahead but suffering and real death—complete annihilation.

It had come to this, that I, a healthy, fortunate man, felt I could no longer live: some irresistible power impelled me to rid myself one way or other of life. I cannot say I wished to kill myself. The power which drew me away from life was stronger, fuller, and more widespread than any mere wish. It was a force similar to the former striving to live, only in a contrary direction. All my strength drew me away from life.

The thought of self-destruction now came to me as naturally as thoughts of how to improve my life had come formerly. And it was so seductive that I had to be cunning with myself lest I should carry it out too hastily. I did not wish to hurry, because I wanted to use all efforts to disentangle the matter.

“If I cannot unravel matters, there will always be time.” And it was then that I, a man favored by fortune, hid a cord from myself lest I should hang myself from the crosspiece of the partition in my room where I undressed alone every evening, and I ceased to go out shooting with a gun lest I should be tempted by so easy a way of ending my life. I did not myself know what I wanted: I feared life, desired to escape from it, yet still hoped something of it.

And all this befell me at a time when all around me I had what is considered complete good fortune. I was not yet fifty; I had a good wife who loved me and whom I loved, good children, and a large estate which without much effort on my part improved and increased. I was respected by my relations and acquaintances more than at any previous time. I was praised by others and without much self-deception could consider that my name was famous.

And far from being insane or mentally diseased, I enjoyed on the contrary a strength of mind and body such as I have seldom met with among men of my kind; physically I could keep up with the peasants at mowing, and mentally I could work for eight and ten hours at a stretch without experiencing any ill results from such exertion. And in this situation I came to this—that I could not live, and, fearing death, had to employ cunning with myself to avoid taking my own life.

My mental condition presented itself to me in this way: my life is a stupid and spiteful joke someone has played on me. Though I did not acknowledge a “someone” who created me, yet such a presentation—that someone had played an evil and stupid joke on me by placing me in the world—was the form of expression that suggested itself most naturally to me.

Involuntarily it appeared to me that there, somewhere, was someone who amused himself by watching how I lived for thirty or forty years: learning, developing, maturing in body and mind, and how, having with matured mental powers reached the summit of life from which it all lay before me, I stood on that summit—like an arch-fool—seeing clearly that there is nothing in life, and that there has been and will be nothing. And he was amused. …

But whether that “someone” laughing at me existed or not, I was none the better off. I could give no reasonable meaning to any single action or to my whole life. I was only surprised that I could have avoided understanding this from the very beginning—it has been so long known to all. To-day or to-morrow sickness and death will come (they had come already) to those I love or to me; nothing will remain but stench and worms.

Sooner or later my affairs, whatever they may be, will be forgotten, and I shall not exist. Then why go on making any effort? … How can man fail to see this? And how go on living? That is what is surprising! One can only live while one is intoxicated with life; as soon as one is sober it is impossible not to see that it is all a mere fraud and a stupid fraud! That is precisely what it is: there is nothing either amusing or witty about it, it is simply cruel and stupid.

There is an Eastern fable, told long ago, of a traveller overtaken on a plain by an enraged beast. Escaping from the beast he gets into a dry well, but sees at the bottom of the well a dragon that has opened its jaws to swallow him. And the unfortunate man, not daring to climb out lest he should be destroyed by the enraged beast, and not daring to leap to the bottom of the well lest he should be eaten by the dragon, seizes a twig growing in a crack in the well and clings to it.

His hands are growing weaker and he feels he will soon have to resign himself to the destruction that awaits him above or below, but still he clings on. Then he sees that two mice, a black one and a white one, go regularly round and round the stem of the twig to which he is clinging and gnaw at it. And soon the twig itself will snap and he will fall into the dragon’s jaws.

The traveller sees this and knows that he will inevitably perish; but while still hanging he looks around, sees some drops of honey on the leaves of the twig, reaches them with his tongue and licks them. So I too clung to the twig of life, knowing that the dragon of death was inevitably awaiting me, ready to tear me to pieces; and I could not understand why I had fallen into such torment.

I tried to lick the honey which formerly consoled me, but the honey no longer gave me pleasure, and the white and black mice of day and night gnawed at the branch by which I hung. I saw the dragon clearly and the honey no longer tasted sweet. I only saw the unescapable dragon and the mice, and I could not tear my gaze from them. and this is not a fable but the real unanswerable truth intelligible to all.

The deception of the joys of life which formerly allayed my terror of the dragon now no longer deceived me. No matter how often I may be told, “You cannot understand the meaning of life so do not think about it, but live,” I can no longer do it: I have already done it too long. I cannot now help seeing day and night going round and bringing me to death. That is all I see, for that alone is true. All else is false.

The two drops of honey which diverted my eyes from the cruel truth longer than the rest: my love of family, and of writing—art as I called it—were no longer sweet to me.

“Family” … said I to myself. But my family—wife and children—are also human. They are placed just as I am: they must either live in a lie or see the terrible truth. Why should they live? Why should I love them, guard them, bring them up, or watch them? That they may come to the despair that I feel, or else be stupid? Loving them, I cannot hide the truth from them: each step in knowledge leads them to the truth. And the truth is death.

“Art, poetry?” … Under the influence of success and the praise of men, I had long assured myself that this was a thing one could do though death was drawing near—death which destroys all things, including my work and its remembrance; but soon I saw that that too was a fraud. It was plain to me that art is an adornment of life, an allurement to life.

But life had lost its attraction for me, so how could I attract others? As long as I was not living my own life but was borne on the waves of some other life—as long as I believed that life had a meaning, though one I could not express—the reflection of life in poetry and art of all kinds afforded me pleasure: it was pleasant to look at life in the mirror of art.

But when I began to seek the meaning of life and felt the necessity of living my own life, that mirror became for me unnecessary, superfluous, ridiculous, or painful. I could no longer soothe myself with what I now saw in the mirror, namely, that my position was stupid and desperate. It was all very well to enjoy the sight when in the depth of my soul I believed that my life had a meaning. Then the play of lights—comic, tragic, touching, beautiful, and terrible—in life amused me.

No sweetness of honey could be sweet to me when I saw the dragon and saw the mice gnawing away my support.

Nor was that all. Had I simply understood that life had no meaning I could have borne it quietly, knowing that that was my lot. But I could not satisfy myself with that. Had I been like a man living in a wood from which he knows there is no exit, I could have lived; but I was like one lost in a wood who, horrified at having lost his way, rushes about wishing to find the road. He knows that each step he takes confuses him more and more, but still he cannot help rushing about.

It was indeed terrible. And to rid myself of the terror I wished to kill myself. I experienced terror at what awaited me—knew that that terror was even worse than the position I was in, but still I could not patiently await the end. However convincing the argument might be that in any case some vessel in my heart would give way, or something would burst and all would be over, I could not patiently await that end.

The horror of darkness was too great, and I wished to free myself from it as quickly as possible by noose or bullet. that was the feeling which drew me most strongly towards suicide.

V

“But perhaps I have overlooked something, or misunderstood something?” said I to myself several times. “It cannot be that this condition of despair is natural to man!” And I sought for an explanation of these problems in all the branches of knowledge acquired by men. I sought painfully and long, not from idle curiosity or listlessly, but painfully and persistently day and night—sought as a perishing man seeks for safety—and I found nothing.

I sought in all the sciences, but far from finding what I wanted, became convinced that all who like myself had sought in knowledge for the meaning of life had found nothing. And not only had they found nothing, but they had plainly acknowledged that the very thing which made me despair—namely the senselessness of life—is the one indubitable thing man can know.

I sought everywhere; and thanks to a life spent in learning, and thanks also to my relations with the scholarly world, I had access to scientists and scholars in all branches of knowledge, and they readily showed me all their knowledge, not only in books but also in conversation, so that I had at my disposal all that science has to say on this question of life.

I was long unable to believe that it gives no other reply to life’s questions than that which it actually does give. It long seemed to me, when I saw the important and serious air with which science announces its conclusions which have nothing in common with the real questions of human life, that there was something I had not understood.

I long was timid before science, and it seemed to me that the lack of conformity between the answers and my questions arose not by the fault of science but from my ignorance, but the matter was for me not a game or an amusement but one of life and death, and I was involuntarily brought to the conviction that my questions were the only legitimate ones, forming the basis of all knowledge, and that I with my questions was not to blame, but science if it pretends to reply to those questions.

My question—that which at the age of fifty brought me to the verge of suicide—was the simplest of questions, lying in the soul of every man from the foolish child to the wisest elder: it was a question without an answer to which one cannot live, as I had found by experience. It was: “What will come of what I am doing to-day or shall do tomorrow? What will come of my whole life?”

Differently expressed, the question is: “Why should I live, why wish for anything, or do anything?” It can also be expressed thus: “Is there any meaning in my life that the inevitable death awaiting me does not destroy?”

To this one question, variously expressed, I sought an answer in science. And I found that in relation to that question all human knowledge is divided as it were into two opposite hemispheres at the ends of which are two poles: the one a negative and the other a positive; but that neither at the one nor the other pole is there an answer to life’s questions.

The one series of sciences seems not to recognize the question, but replies clearly and exactly to its own independent questions: that is the series of experimental sciences, and at the extreme end of it stands mathematics. The other series of sciences recognizes the question, but does not answer it; that is the series of abstract sciences, and at the extreme end of it stands metaphysics.

From early youth I had been interested in the abstract sciences, but later the mathematical and natural sciences attracted me, and until I put my question definitely to myself, until that question had itself grown up within me urgently demanding a decision, I contented myself with those counterfeit answers which science gives.

Now in the experimental sphere I said to myself: “Everything develops and differentiates itself, moving towards complexity and perfection, and there are laws directing this movement. You are a part of the whole. Having learnt as far as possible the whole, and having learnt the law of evolution, you will understand also your place in the whole and will know yourself.” Ashamed as I am to confess it, there was a time when I seemed satisfied with that.

It was just the time when I was myself becoming more complex and was developing. My muscles were growing and strengthening, my memory was being enriched, my capacity to think and understand was increasing, I was growing and developing; and feeling this growth in myself it was natural for me to think that such was the universal law in which I should find the solution of the question of my life. But a time came when the growth within me ceased.

I felt that I was not developing, but fading, my muscles were weakening, my teeth falling out, and I saw that the law not only did not explain anything to me, but that there never had been or could be such a law, and that I had taken for a law what I had found in myself at a certain period of my life.

I regarded the definition of that law more strictly, and it became clear to me that there could be no law of endless development; it became clear that to say, “in infinite space and time everything develops, becomes more perfect and more complex, is differentiated,” is to say nothing at all. These are all words with no meaning, for in the infinite there is neither complex nor simple, neither forward nor backward, nor better or worse.

Above all, my personal question, “What am I with my desires?” remained quite unanswered. And I understood that those sciences are very interesting and attractive, but that they are exact and clear in inverse proportion to their applicability to the question of life: the less their applicability to the question of life, the more exact and clear they are, while the more they try to reply to the question of life, the more obscure and unattractive they become.

If one turns to the division of sciences which attempt to reply to the questions of life—to physiology, psychology, biology, sociology—one encounters an appalling poverty of thought, the greatest obscurity, a quite unjustifiable pretension to solve irrelevant questions, and a continual contradiction of each authority by others and even by himself.

If one turns to the branches of science which are not concerned with the solution of the questions of life, but which reply to their own special scientific questions, one is enraptured by the power of man’s mind, but one knows in advance that they give no reply to life’s questions. Those sciences simply ignore life’s questions.

They say: “To the question of what you are and why you live we have no reply, and are not occupied with that; but if you want to know the laws of light, of chemical combinations, the laws of development of organisms, if you want to know the laws of bodies and their form, and the relation of numbers and quantities, if you want to know the laws of your mind, to all that we have clear, exact and unquestionable replies.”

In general the relation of the experimental sciences to life’s question may be expressed thus: Question: “Why do I live?” Answer: “In infinite space, in infinite time, infinitely small particles change their forms in infinite complexity, and when you have understood the laws of those mutations of form you will understand why you live on the earth.”

Then in the sphere of abstract science I said to myself: “All humanity lives and develops on the basis of spiritual principles and ideals which guide it. Those ideals are expressed in religions, in sciences, in arts, in forms of government. Those ideals become more and more elevated, and humanity advances to its highest welfare.

I am part of humanity, and therefore my vocation is to forward the recognition and the realization of the ideals of humanity.” And at the time of my weak-mindedness I was satisfied with that; but as soon as the question of life presented itself clearly to me, those theories immediately crumbled away.

Not to speak of the unscrupulous obscurity with which those sciences announce conclusions formed on the study of a small part of mankind as general conclusions; not to speak of the mutual contradictions of different adherents of this view as to what are the ideals of humanity; the strangeness, not to say stupidity, of the theory consists in the fact that in order to reply to the question facing each man: “What am I?” or “Why do I live?” or “What must I do?” one has first to decide the question: “What is the life of the whole?” (which is to him unknown and of which he is acquainted with one tiny part in one minute period of time).

To understand what he is, man must first understand all this mysterious humanity, consisting of people such as himself who do not understand one another.

I have to confess that there was a time when I believed this. It was the time when I had my own favorite ideals justifying my own caprices, and I was trying to devise a theory which would allow one to consider my caprices as the law of humanity. But as soon as the question of life arose in my soul in full clearness that reply at once flew to dust.

And I understood that as in the experimental sciences there are real sciences, and semi-sciences which try to give answers to questions beyond their competence, so in this sphere there is a whole series of most diffused sciences which try to reply to irrelevant questions. Semi-sciences of that kind, the juridical and the social-historical, endeavor to solve the questions of a man’s life by pretending to decide, each in its own way, the question of the life of all humanity.

But as in the sphere of man’s experimental knowledge one who sincerely inquires how he is to live cannot be satisfied with the reply—"Study in endless space the mutations, infinite in time and in complexity, of innumerable atoms, and then you will understand your life”—so also a sincere man cannot be satisfied with the reply: “Study the whole life of humanity of which we cannot know either the beginning or the end, of which we do not even know a small part, and then you will understand your own life.” And like the experimental semi-sciences, so these other semi-sciences are the more filled with obscurities, inexactitudes, stupidities, and contradictions, the further they diverge from the real problems.

The problem of experimental science is the sequence of cause and effect in material phenomena. It is only necessary for experimental science to introduce the question of a final cause for it to become nonsensical. The problem of abstract science is the recognition of the primordial essence of life. It is only necessary to introduce the investigation of consequential phenomena (such as social and historical phenomena) and it also becomes nonsensical.

Experimental science only then gives positive knowledge and displays the greatness of the human mind when it does not introduce into its investigations the question of an ultimate cause. And, on the contrary, abstract science is only then science and displays the greatness of the human mind when it puts quite aside questions relating to the consequential causes of phenomena and regards man solely in relation to an ultimate cause.

Such in this realm of science—forming the pole of the sphere—is metaphysics or philosophy. That science states the question clearly: “What am I, and what is the universe? And why do I exist, and why does the universe exist?” And since it has existed it has always replied in the same way.

Whether the philosopher calls the essence of life existing within me, and in all that exists, by the name of “idea,” or “substance,” or “spirit,” or “will,” he says one and the same thing: that this essence exists and that I am of that same essence; but why it is he does not know, and does not say, if he is an exact thinker. I ask: “Why should this essence exist? What results from the fact that it is and will be?” … And philosophy not merely does not reply, but is itself only asking that question.

And if it is real philosophy all its labor lies merely in trying to put that question clearly. And if it keeps firmly to its task it cannot reply to the question otherwise than thus: “What am I, and what is the universe?” “All and nothing”; and to the question “Why?” by “I do not know.”

So that however I may turn these replies of philosophy, I can never obtain anything like an answer—and not because, as in the clear experimental sphere, the reply does not relate to my question, but because here, though all the mental work is directed just to my question, there is no answer, but instead of an answer one gets the same question, only in a complex form.

VI

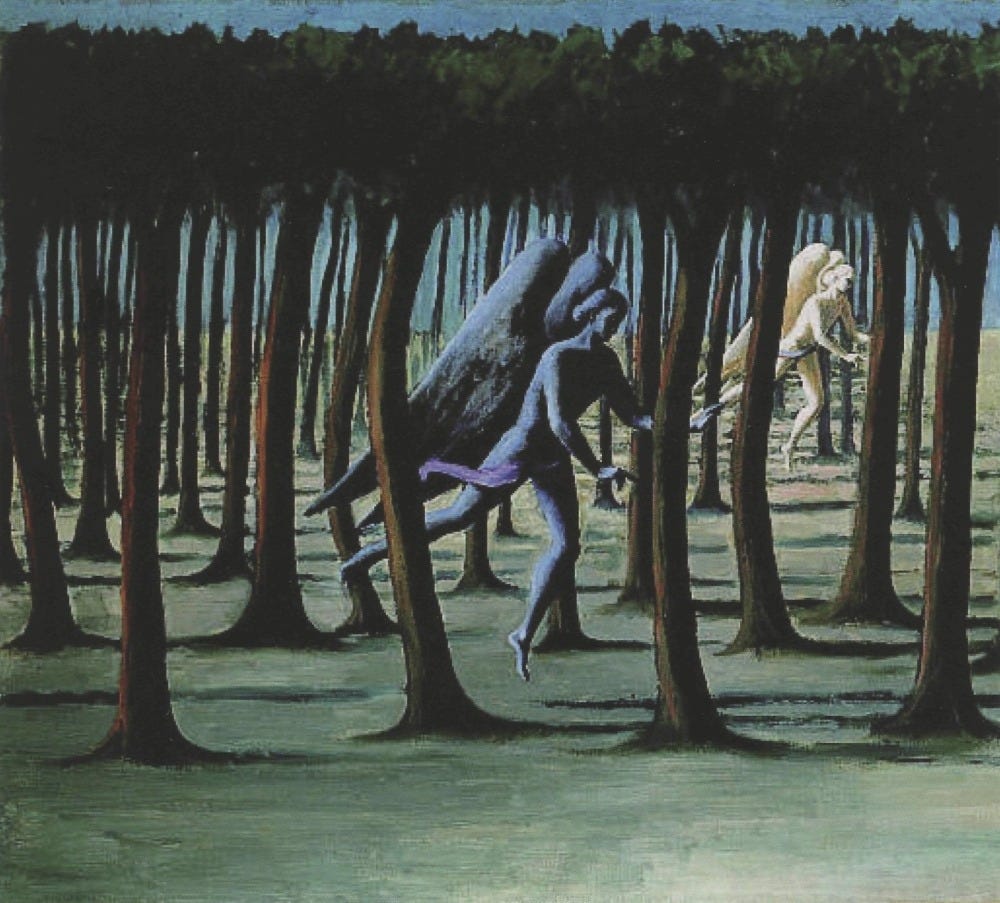

In my search for answers to life’s questions I experienced just what is felt by a man lost in a forest.

He reaches a glade, climbs a tree, and clearly sees the limitless distance, but sees that his home is not and cannot be there; then he goes into the dark wood and sees the darkness, but there also his home is not.

So I wandered in that wood of human knowledge, amid the gleams of mathematical and experimental science which showed me clear horizons, but in a direction where there could be no home, and also amid the darkness of the abstract sciences where I was immersed in deeper gloom the further I went, and where I finally convinced myself that there was, and could be, no exit.

Yielding myself to the bright side of knowledge, I understood that I was only diverting my gaze from the question. However alluringly clear those horizons which opened out before me might be, however alluring it might be to immerse oneself in the limitless expanse of those sciences, I already understood that the clearer they were the less they met my need and the less they applied to my question.

“I know,” said I to myself, “what science so persistently tries to discover, and along that road there is no reply to the question as to the meaning of my life.” In the abstract sphere I understood that notwithstanding the fact, or just because of the fact, that the direct aim of science is to reply to my question, there is no reply but that which I have myself already given: “What is the meaning of my life?” “There is none.” Or: “What will come of my life?” “Nothing.” Or: “Why does everything exist that exists, and why do I exist?” “Because it exists.”

Inquiring for one region of human knowledge, I received an innumerable quantity of exact replies concerning matters about which I had not asked: about the chemical constituents of the stars, about the movement of the sun towards the constellation Hercules, about the origin of species and of man, about the forms of infinitely minute imponderable particles of ether; but in this sphere of knowledge the only answer to my question, “What is the meaning of my life?” was: “You are what you call your ‘life’; you are a transitory, casual cohesion of particles.

The mutual interactions and changes of these particles produce in you what you call your ‘life’. That cohesion will last some time; afterwards the interaction of these particles will cease and what you call ‘life’ will cease, and so will all your questions. You are an accidentally united little lump of something. That little lump ferments. The little lump calls that fermenting its ‘life.’

The lump will disintegrate and there will be an end of the fermenting and of all the questions.” So answers the clear side of science and cannot answer otherwise if it strictly follows its principles.

From such a reply one sees that the reply does not answer the question. I want to know the meaning of my life, but that it is a fragment of the infinite, far from giving it a meaning destroys its every possible meaning. The obscure compromises which that side of experimental exact science makes with abstract science when it says that the meaning of life consists in development and in co-operation with development, owing to their inexactness and obscurity cannot be considered as replies.

The other side of science—the abstract side—when it holds strictly to its principles, replying directly to the question, always replies, and in all ages has replied, in one and the same way: “The world is something infinite and incomprehensible. Human life is an incomprehensible part of that incomprehensible ‘all’.” Again I exclude all those compromises between abstract and experimental sciences which supply the whole ballast of the semi-sciences called juridical, political, and historical.

In those semi-sciences the conception of development and progress is again wrongly introduced, only with this difference, that there it was the development of everything while here it is the development of the life of mankind. The error is there as before: development and progress in infinity can have no aim or direction, and, as far as my question is concerned, no answer is given.

In truly abstract science, namely in genuine philosophy—not in that which Schopenhauer calls “professorial philosophy” which serves only to classify all existing phenomena in new philosophic categories and to call them by new names—where the philosopher does not lose sight of the essential question, the reply is always one and the same—the reply given by Socrates, Schopenhauer, Solomon, and Buddha.

“We approach truth only inasmuch as we depart from life,” said Socrates when preparing for death. For what do we, who love truth, strive after in life? To free ourselves from the body, and from all the evil that is caused by the life of the body! If so, then how can we fail to be glad when death comes to us?

“The wise man seeks death all his life and therefore death is not terrible to him.”

And Schopenhauer says:

“Having recognized the inmost essence of the world as will, and all its phenomena—from the unconscious working of the obscure forces of Nature up to the completely conscious action of man—as only the objectivity of that will, we shall in no way avoid the conclusion that together with the voluntary renunciation and self-destruction of the will all those phenomena also disappear, that constant striving and effort without aim or rest on all the stages of objectivity in which and through which the world exists; the diversity of successive forms will disappear, and together with the form all the manifestations of will, with its most universal forms, space and time, and finally its most fundamental form—subject and object.

Without will there is no concept and no world. Before us, certainly, nothing remains. But what resists this transition into annihilation, our nature, is only that same wish to live—Wille zum Leben—which forms ourselves as well as our world. That we are so afraid of annihilation or, what is the same thing, that we so wish to live, merely means that we are ourselves nothing else but this desire to live, and know nothing but it.

And so what remains after the complete annihilation of the will, for us who are so full of the will, is, of course, nothing; but on the other hand, for those in whom the will has turned and renounced itself, this so real world of ours with all its suns and milky way is nothing.”

“Vanity of vanities,” says Solomon—"vanity of vanities—all is vanity. What profit hath a man of all his labor which he taketh under the sun? One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever. … The thing that hath been, is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun. Is there anything whereof it may be said, See, this is new? it hath been already of old time, which was before us.

There is no remembrance of former things; neither shall there be any remembrance of things that are to come with those that shall come after. I the Preacher was King over Israel in Jerusalem. And I gave my heart to seek and search out by wisdom concerning all that is done under heaven: this sore travail hath God given to the sons of man to be exercised therewith. I have seen all the works that are done under the sun; and behold, all is vanity and vexation of spirit. …

I communed with my own heart, saying, Lo, I am come to great estate, and have gotten more wisdom than all they that have been before me over Jerusalem: yea, my heart hath great experience of wisdom and knowledge. And I gave my heart to know wisdom, and to know madness and folly: I perceived that this also is vexation of spirit. For in much wisdom is much grief: and he that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow.

I said in my heart, Go to now, I will prove thee with mirth, therefore enjoy pleasure: and behold this also is vanity. I said of laughter, It is mad: and of mirth, What doeth it? I sought in my heart how to cheer my flesh with wine, and while my heart was guided by wisdom, to lay hold on folly, till I might see what it was good for the sons of men that they should do under heaven the number of the days of their life.

I made me great works; I builded me houses; I planted me vineyards: I made me gardens and orchards, and I planted trees in them of all kinds of fruits: I made me pools of water, to water therefrom the forest where trees were reared: I got me servants and maidens, and had servants born in my house; also I had great possessions of herds and flocks above all that were before me in Jerusalem: I gathered me also silver and gold and the peculiar treasure from kings and from the provinces: I got me men singers and women singers; and the delights of the sons of men, as musical instruments and that of all sorts.

So I was great, and increased more than all that were before me in Jerusalem: also my wisdom remained with me. And whatever mine eyes desired I kept not from them. I withheld not my heart from any joy. … Then I looked on all the works that my hands had wrought, and on the labour that I had labored to do: and, behold, all was vanity and vexation of spirit, and there was no profit from them under the sun. And I turned myself to behold wisdom, and madness, and folly. …

But I perceived that one event happeneth to them all. Then said I in my heart, As it happeneth to the fool, so it happeneth even to me, and why was I then more wise? Then I said in my heart, that this also is vanity. For there is no remembrance of the wise more than of the fool for ever; seeing that which now is in the days to come shall all be forgotten. And how dieth the wise man? as the fool.

Therefore I hated life; because the work that is wrought under the sun is grievous unto me: for all is vanity and vexation of spirit. Yea, I hated all my labor which I had taken under the sun: seeing that I must leave it unto the man that shall be after me. … For what hath man of all his labor, and of the vexation of his heart, wherein he hath labored under the sun? For all his days are sorrows, and his travail grief; yea, even in the night his heart taketh no rest. This is also vanity.

Man is not blessed with security that he should eat and drink and cheer his soul from his own labor. … All things come alike to all: there is one event to the righteous and to the wicked; to the good and to the evil: to the clean and to the unclean; to him that sacrificeth and to him that sacrificeth not; as is the good, so is the sinner; and he that sweareth, as he that feareth an oath.

This is an evil in all that is done under the sun, that there is one event unto all; yea, also the heart of the sons of men is full of evil, and madness is in their heart while they live, and after that they go to the dead. For him that is among the living there is hope: for a living dog is better than a dead lion. For the living know that they shall die: but the dead know not any thing, neither have they any more a reward; for the memory of them is forgotten.

Also their love, and their hatred, and their envy, is now perished; neither have they any more a portion for ever in any thing that is done under the sun.”

So said Solomon, or whoever wrote those words.

And this is what the Indian wisdom tells:

Sakya Muni, a young, happy prince, from whom the existence of sickness, old age, and death had been hidden, went out to drive and saw a terrible old man, toothless and slobbering.

The prince, from whom till then old age had been concealed, was amazed, and asked his driver what it was, and how that man had come to such a wretched and disgusting condition, and when he learnt that this was the common fate of all men, that the same thing inevitably awaited him—the young prince—he could not continue his drive, but gave orders to go home, that he might consider this fact. So he shut himself up alone and considered it.

And he probably devised some consolation for himself, for he subsequently again went out to drive, feeling merry and happy. But this time he saw a sick man. He saw an emaciated, livid, trembling man with dim eyes. The prince, from whom sickness had been concealed, stopped and asked what this was.

And when he learnt that this was sickness, to which all men are liable, and that he himself—a healthy and happy prince—might himself fall ill to-morrow, he again was in no mood to enjoy himself but gave orders to drive home, and again sought some solace, and probably found it, for he drove out a third time for pleasure. But this third time he saw another new sight: he saw men carrying something. “What is that?” “A dead man.” “What does dead mean?” asked the prince.

He was told that to become dead means to become like that man. The prince approached the corpse, uncovered it, and looked at it. “What will happen to him now?” asked the prince. He was told that the corpse would be buried in the ground.

“Why?” “Because he will certainly not return to life, and will only produce a stench and worms.” “And is that the fate of all men? Will the same thing happen to me? Will they bury me, and shall I cause a stench and be eaten by worms?” “Yes.” “Home! I shall not drive out for pleasure, and never will so drive out again!”

And Sakya Muni could find no consolation in life, and decided that life is the greatest of evils; and he devoted all the strength of his soul to free himself from it, and to free others; and to do this so that, even after death, life shall not be renewed any more but be completely destroyed at its very roots. So speaks all the wisdom of India.

These are the direct replies that human wisdom gives when it replies to life’s question.

“The life of the body is an evil and a lie. Therefore the destruction of the life of the body is a blessing, and we should desire it,” says Socrates.

“Life is that which should not be—an evil; and the passage into Nothingness is the only good in life,” says Schopenhauer.

“All that is in the world—folly and wisdom and riches and poverty and mirth and grief—is vanity and emptiness. Man dies and nothing is left of him. And that is stupid,” says Solomon.

“To live in the consciousness of the inevitability of suffering, of becoming enfeebled, of old age and of death, is impossible—we must free ourselves from life, from all possible life,” says Buddha.

And what these strong minds said has been said and thought and felt by millions upon millions of people like them. And I have thought it and felt it.

So my wandering among the sciences, far from freeing me from my despair, only strengthened it. One kind of knowledge did not reply to life’s question, the other kind replied directly confirming my despair, indicating not that the result at which I had arrived was the fruit of error or of a diseased state of my mind, but on the contrary that I had thought correctly, and that my thoughts coincided with the conclusions of the most powerful of human minds.

It is no good deceiving oneself. It is all vanity! Happy is he who has not been born: death is better than life, and one must free oneself from life.