Philosophy is the art of dying, ars moriendi. It claims that death is the one thing I truly own, that I keep for myself. Death is my “ownmost possibility,” said Heidegger, completely unique to me. No one else can do it for me or with me. It is final and unrepeatable.

But this is obviously false. As those of us who have experienced the death of a child can tell you, my child’s death is more fundamental than my own.

When the Virgin Mary brought Jesus to the temple on the fortieth day after his birth, the prophet Simeon told her, “A sword shall pierce through your own soul also” (Luke 2:35). Simeon spoke of a death blow, a fatality to which the Mother of God succumbed on Golgotha at the crucifixion.

St Maximus the Confessor, the probable author of a seventh-century Greek biography of the Virgin Mary, writes, “O Mother of Christ, a sword pierced through your soul as Simeon told you. Then the nails that pierced the Lord’s hands pierced your heart. These sufferings overcame you more than [Jesus].”1

Unlike philosophy, Christianity teaches that the death of another can become mine too.

It also teaches life after death, and not simply in the sense of afterlife. Dying with and in her Son, Mary also rose with him on Easter morning. Mary is the paradigmatic example of the Christian art of living after dying.

But what is living after such a death?

St Maximus reports that Mary’s life in Jerusalem as a leader in the emerging Christian church was marked by embodied acts of mercy to strangers and enemies, though he is vague on the specifics. He describes her simply as the “mother of the poor and needy…because for our sake the rich one was made poor in order to enrich us, the downcast and poor.”2

This muted account of the Virgin Mary’s later life offers only a hint of what living after dying means—to live for others in acts of God-like compassion—but it is left to others to paint a fuller picture.

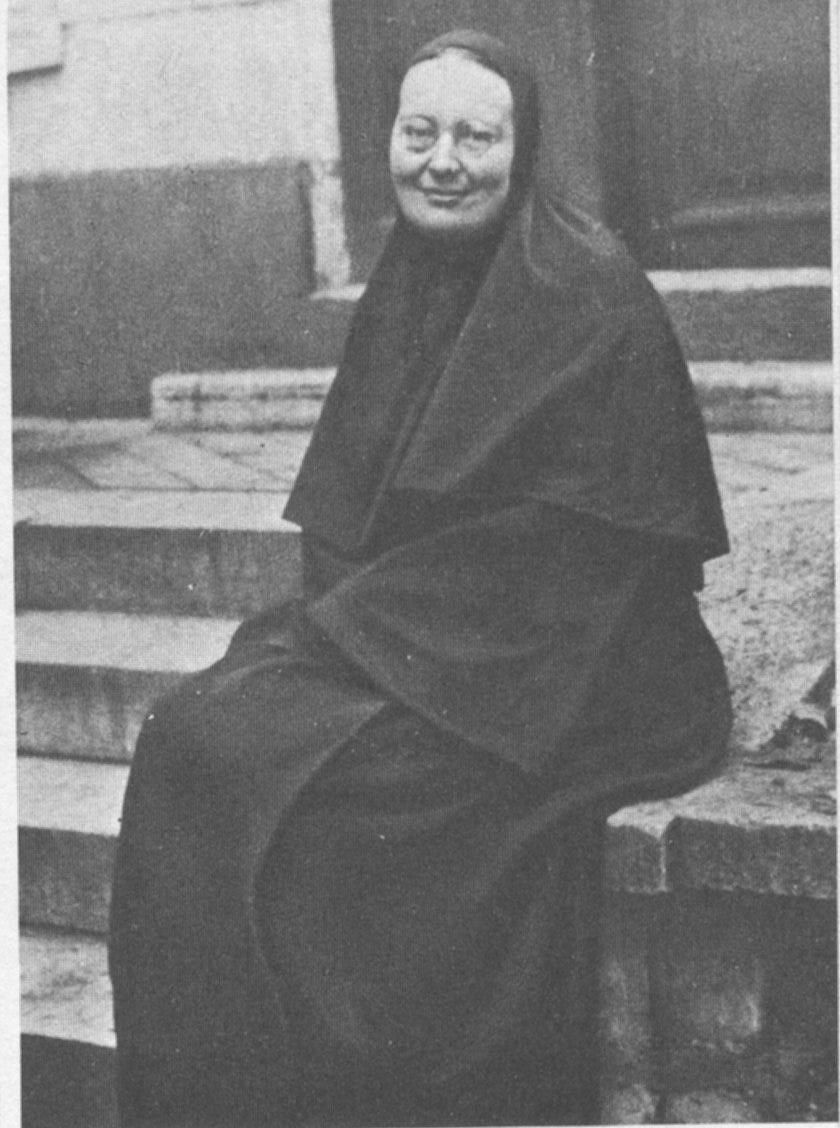

The saint Mother Maria Skobtsova, an Eastern Orthodox nun, poet, theologian, and apostle to the poor, was someone who died halfway through her eventful life —via the death of two of her children. Mother Maria’s luminous life after death is perhaps the most important thing she can teach.

The poet and the revolution

Mother Maria Skobtsova was born Elizaveta (Liza) Pilenko in 1891 into a wealthy and well-connected Russo-Ukrainian family. After the death of her father, her family moved from their estate on the Black Sea to the imperial capital of St Petersburg.

Liza, while still a teenager, attached herself to the esoteric and at times transgressive poets of the “Russian Silver Age,” Alexander Blok, Anna Akhmatova, Vyacheslav Ivanov, and Osip Mandelstam among them. They saw great potential in her, and championed her first volume of poetry, from 1912.

Although she relished the late nights into early mornings spent talking politics, poetry, and mysticism, her sense of idealism prohibited her from throwing herself completely into the world of words. People were suffering, and they were just talking, high in Ivanov’s tower-like apartment!

For her, there was something lethal about such passivity. Blok wrote to her when they first met, “Run, run from us, the dying ones!” After lingering a few years with them, she did.

Liza joined the Socialist-Revolutionary Party, and became the deputy mayor of Anapa, her hometown on the Black Sea, in 1918. Within a year, she faced trial by a hostile White Army military tribunal, who had retaken the town. Although she had no special party loyalty and wished only “for justice and for the relief of suffering,” they saw her as just another Communist.

Convicted, she faced a sentence that could have ranged anywhere from a three-ruble fine to execution by firing squad. However, the sentence she received was minimal, thanks to the intervention of one of the judges, Liza’s former schoolmaster Daniel Skobtsov. He pitied her and her daughter Gaiana (perhaps by a failed marriage, perhaps by another lover). They married just days after the trial.

After the Bolsheviks took power, the Skobtsovs fled the Soviet Union, settling in Paris as stateless refugees. They set up a new life alongside tens of thousands of other Russian refugees, both monarchist Whites and not-left-enough socialists. With Daniel, she had two more children: Anastasia and Yuri.

From Liza Skobtsova to Mother Maria

Liza had been baptized as an infant, and after a period of atheism following the death of her father when she was 14 years old, she took on faith for herself in her last years in Russia. Her 1916 book of poetry, Ruth, reflects her growing attraction to Christ, first as a historical figure, then as living Savior. Here is one short stanza from this long work:

O Lord, do not leave me in the night,

Exhausted, hungry and barefoot,

Sprinkle me with cool dew,

Knock upon my soul like a weary traveler.3

In Paris, she absorbed the writings of the intellectual movement often called “Russian religious thought,” a stream of thinking influenced by Orthodox theology and German philosophy systematized by philosopher Vladimir Soloviev (d. 1900). This movement was carried into Europe by fellow exiles Nicholas Berdyaev and Fr Sergius Bulgakov, two of Liza’s closest friends and mentors in Paris.

Liza and a circle of Orthodox émigré thinkers embarked on a project: to unearth, without fear of ecclesiastical or political censorship, the riches of the Orthodox tradition and to explore the outer reaches of its philosophical and theological possibilities in conversation with European thinkers like Jacques Maritain, Emmanuel Mounier, and Karl Barth.

Liza led the “social” side of this largely intellectual project within the Orthodox Church in exile in Western Europe, giving lectures and writing pamphlets on Orthodox social theology, a topic that still has never been adequately explored. However, as with the poets in St Petersburg, Liza began to believe there were limits to social theology as a merely intellectual exercise. She wanted to take action.

In her travels around Europe lecturing at youth camps and conferences, strangers approached her, lining up to talk to her after lectures, not about the content of her research, but about their own struggles, sorrows, and fears. She wrote,

“A queue would form by the door as if outside a confessional. There would be people wanting to pour out their hearts, to tell of some terrible grief which had burdened them for years, of pangs of conscience which gave them no peace. In such slums it is no use speaking of faith in God, of Christ or of the Church. What is needed here is not religious preaching, but the simplest thing of all: compassion.”4 For Liza, compassion—“co-suffering” and “co-feeling” as she would later articulate it—was a gift given to her by the Spirit of God.

Yet with this newfound discovery of inner fullness, heartbreak came when her infant daughter Anastasia died. In the winter of 1926, the Skobtsov family contracted influenza. All recovered except for the baby. She was admitted to the Pasteur Institute and diagnosed with meningitis. Liza was allowed to stay day and night to care for her, but to no avail.

The death of Anastasia was Liza’s Golgotha. As she would put it later, when her older daughter Gaiana also died, “Now I know what death is.”

The death of a child is a death that penetrates to the center of the soul. It threatens to black it out entirely. Liza wrote a poem after Gaiana’s death:

A solemn, luminescent gift—

You granted me death. To languish in.

The soul, burned in the conflagration,

Slowly sinks forever into the night.

At its bottom, only coal, black and reddish,

It needs to tuck itself away, keep silent.

But in my heart, You burned with eternal fire

The seal of death’s baptism.

Liza discovered after the deaths of Anastasia and Gaiana that her remarkable gift of compassion had a profoundly maternal dimension. She wrote, “I became aware of a new and special, broad, and all-embracing motherhood. I returned from that cemetery a different person. I saw a new road before me and a new meaning in life.”5 She put it similarly in another poem after Gaiana’s death:

You unlocked the heart’s lock through hardships.

Now the road ahead lies like a covering

In all directions. Sometimes to be a mother,

Sometimes placed over the churchyard,

Whatever else You command me to be,—I do not know.

Liza came to see that this newfound, all-embracing motherhood, full of potential, could only be realized by a radical change. With her husband Daniel’s consent and the blessing of the church, she divorced again and accepted monastic tonsure, taking the name Mother Maria. From now on, her life would be defined by the great “Mother Maria,” the “All-compassionate Mother,” as the Virgin Mary is called in Eastern Orthodox liturgical hymnography.

Orthodox Action

Following the example of the Virgin Mary, Mother Maria’s life after dying was to be a life of compassion for others. Mother Maria explored the traditional forms of Orthodox monasticism in secluded compounds dedicated to prayer, but could not reconcile her calling to universal motherhood with the demand for the absolute renunciation of the world.

Rather than being cut off, she wrote, the world had to be pierced with love: “The more we go out into the world, the more we give ourselves to the world, the less we are of the world. For the worldly do not give the world an offering of themselves.”6

Armed with her expansive capacity for compassion, instead of joining a monastery, Mother Maria founded a different kind of collective life, an organization called “Orthodox Action.”

Obtaining a large house in an impoverished section of Paris, she invited in the poor and the neglected, housed, fed, and loved them. The Orthodox Action center included a dining hall, many beds, a roundtable for intellectual discussions, and a chapel. Her motto: “Each person is the very icon of God incarnate.”

Mother Maria and her co-workers met with some resistance, especially from more conservative émigré Russians who knew of her socialist roots. Her own bishop Metropolitan Evlogy Georgievsky, who nevertheless supported and co-signed her efforts, wrote in his diary, “The old party spirit is still very much in evidence in Mother Maria.” Yet this only strengthened her resolve.

The ambitions of Mother Maria and Orthodox Action were large, and they achieved much success in their charitable efforts in terms of the sheer numbers of meals served over the course of just eight-odd years of existence from 1935-1943. Yet what they sought was not charity but to build “life in common,” even when it was difficult.

Once, a frequent guest at the center, a young drug addict, stole 25 francs. Everyone thought they knew who it was but Mother Maria refused to accuse her. Instead, that evening, she announced that the money had not been stolen, only misplaced, and that she had found it. Immediately the girl who stole the money burst into tears.

She wrote in her manifesto for Orthodox Action at its founding in 1935, “We do not want to be executors of charity—we are building our life in common. It is not our fault that this is not the life of a large state or of humanity as a whole. We deal in the small, and we want to be true to the small.”7

For Orthodox Action, a “life in common” was one that somehow integrated the charitable, liturgical, and intellectual work they did. Though their operation expanded, they wanted never to sacrifice their primary concern for the human person, each of whom is beloved by God.

One of their most moving efforts was to hold funerals for impoverished émigrés who died in Parisian hospitals with no one to bury them. Mother Maria stitched their names on a huge tapestry that hung on the wall of the chapel. Life in common included both the living and the dead.

On the imitation of the Mother of God

In addition to scores of poems, Mother Maria also wrote theological essays late at night after cooking and cleaning. Her notebooks, now in archives at Columbia University, still have carrot peels in between the pages.

In one of her most polished essays, “On the Imitation of the Mother of God,” from 1939, Mother Maria articulated in quite inventive theological terms what she saw as the shape of Christian life: to imitate the Virgin Mary, her living after dying on the cross with Christ.

The cross, she wrote, is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it was a death chosen by the Son of God, his willing and active self-offering. On the other hand, it is the sword that pierced the soul of Mary, an involuntary co-suffering with him. His death was chosen by him, not her; yet she suffered it also, and took it on as her own.

Mary’s co-suffering determined her destiny: in so far as Christ is eternally sacrificed on behalf of the world, her heart is eternally pierced, also on the world’s behalf. She is the compassionate Mother of everyone walking their own path, carrying their own cross. Mother Maria wrote,

“All the countless crosses that mankind takes on its shoulders to follow Christ also become countless swords eternally piercing her maternal heart. She continues to co-participate, co-feel, co-suffer with each human soul, as then on Golgotha.” She continues, “And in this sense she always walks with us on our own way of the cross, she is always there beside us, each of our crosses is a sword for her.”8

In a poem, Mother Maria identifies herself with the Mother of God, co-suffering with others. She walks not to a gloomy and hopeless death, but a “victorious” one:

I will spare nothing,

Desolate, naked.

You, double-edged sword,

Why do you hesitate so, in punishing us?

With no well-ordered systems,

With no subtle philosophies,

My spirit wanders, muddled and mute,

To its victorious Golgotha.

Deserted is the dead sky,

And dead is the deserted earth.

And eternally the Mother gives away

The Son to eternal Golgotha.

For Mother Maria, the “Marian” task of living after dying is to accompany the suffering, to willingly take on maternal compassion, even to the end.

A second death

Mother Maria’s work with Orthodox Action lasted just a few years. After the Nazi invasion of Paris in 1940, Orthodox Action dedicated itself to forging baptismal certificates for Jewish people, saving dozens from arrest and exile to concentration camps over the course of a couple of years. However, this work was eventually discovered by the Gestapo, and Orthodox Action members were arrested.

Mother Maria was put on a train to the notorious Ravensbrück concentration camp. It was there that she died in 1945, reportedly giving her life in another’s stead, taking their place in a gas chamber.

But Mother Maria had already died, long before she was gassed. Her death was not solitary and “ownmost.” It was victorious, and became the cause of rebirth, of joy and of love.

Every moment of life after the death of her children overflowed with grace, which she spilled out for others through her hands, unable to be contained.

My Lord, I embraced life,

I lived with love and fervor.

With love I embrace death.

See, my cup overflows.

At Your feet the cup has fallen.

The life I spilled out before You.9

Stephen J. Shoemaker, The Life of the Virgin: Maximus the Confessor (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 105).

Shoemaker, The Life of the Virgin, 129

This and the poems below translated from A.N. Shustov, ed., Elizaveta Kuzmina-Karavaeva/Mat’ Maria. Stikhotvoreniia i Poemy. P’esy-misterii. Khudozhestvennaia i Avtobiograficheskaia Proza. Pis’ma (Saint Petersburg: Iskusstvo-CPB, 2001), 105, 149-154.

Sergei Hackel, Pearl of Great Price: The Life of Mother Maria Skobtsova 1891-1945 (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1981), 11.

Hackel, Pearl, 16.

Hackel, Pearl, 27.

Mother Maria (Skobtsova), “Pravoslavnoe Delo,” Novyi Grad 10 (1935): 115.

Mother Maria (Skobtsova), “On the Imitation of the Mother of God,” in ibid. Essential Writings, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2003), 69.

A version of this article appeared in German translation in Religion & Gesellschaft in Ost und West 53 (5/2025): 19-21. Thanks to editor Regula Zwahlen and Forum RGOW for permission to publish this article in Cluny, for her translation of the article, and to Daniel Henseler for translating Mother Maria’s poems into German. Some of my translations drew from his.

Do you have a link to the Russian versions of the poems? Thank you.