For a few months we lived in the Tower of Babel. Above, heaven. Above that, God. Between us and the firmament stood a single penthouse apartment, currently undergoing heavy renovations.

The word on the street was that multiple bathrooms and a kitchen were being rearranged up there, a process that reverberated in the human jaw. In the evenings, my husband and I turned our gaze to the jackhammers on high and asked, in all sincerity, “How is there any apartment left to renovate upstairs?” We fell asleep to Reddit-sourced mantras of structural integrity: beware the load-bearing wall. It never occurred to us that the primary risk was not the collapse of our Tower, but something insurance agents would soon translate as a rupture to the “water main.”

We were the good Babylonians: resigned, unambitious renters with no plans to renovate ourselves. If the ceiling fell, it was God’s will.

Most Swiss will tell you that Geneva isn’t really Switzerland, nor Europe, but some other, third, supranational thing. It is a whole collection of cities in one. A crude census puts the diasporas of Southern Europe and the former Yugoslavia alongside the acronymic expat workforce (UN, WTO, UNICEF, ICRC, CERN), alongside the asylum seekers, commodity traders, watchmakers, art dealers, and the Free Port, where much of that art is stored. Then come the actual Swiss, or the French who cross the border every morning in search of higher wages. The passport-rich stick to compounds in the suburbs, and exist in tax and legal brackets of their own.

This is to say there isn’t really a common language or city genevois. And yet public administration works world-famously well.

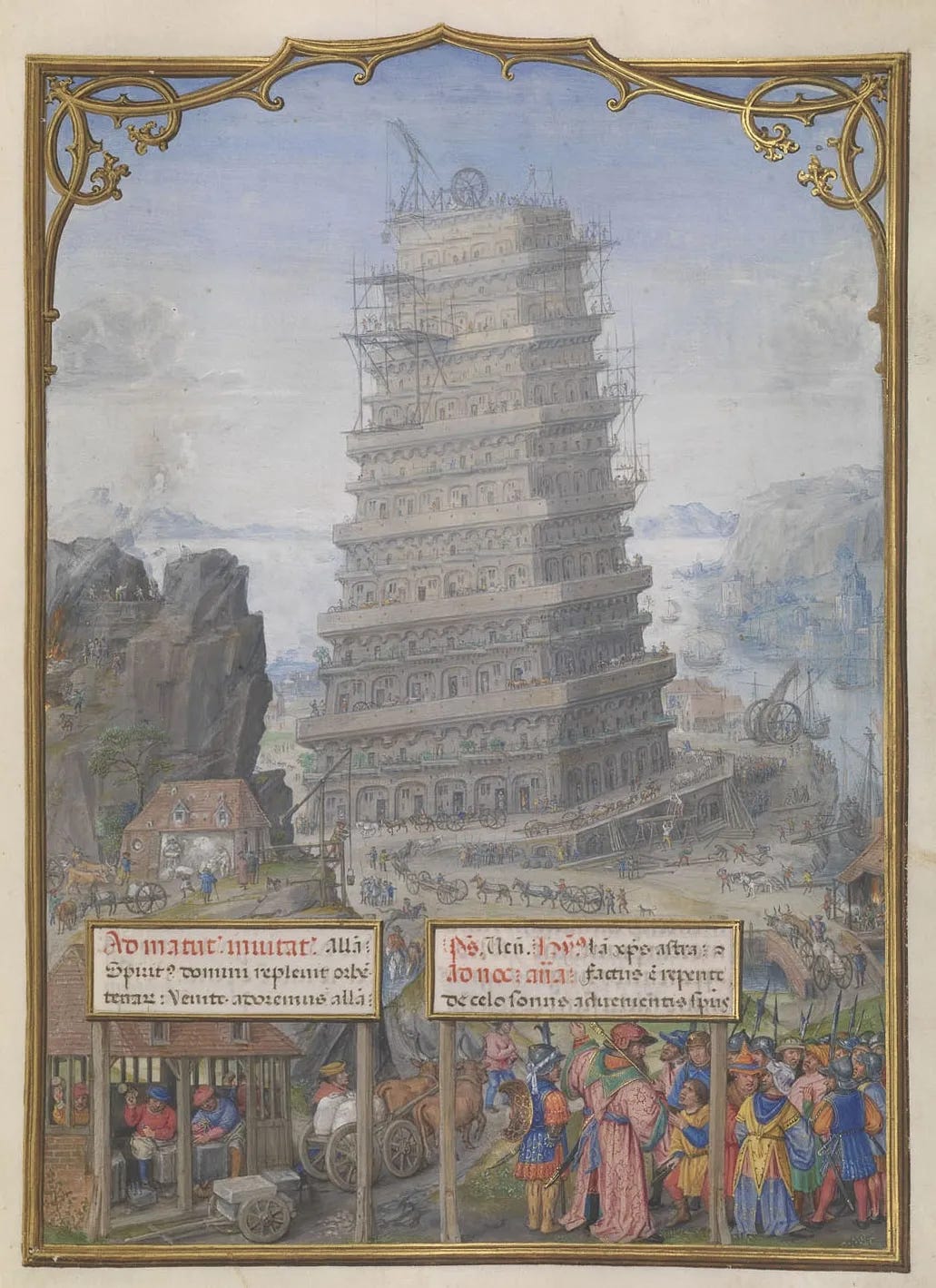

You know the story: Once upon a time, the people of Babel built a tower tall enough to touch heaven and rival God. It was an early experiment in urban mass housing, and a testament to human ingenuity at a time when the whole world was “of one speech and of one tongue.” As a display of hubris, it was all the more astonishing for arriving just after the Flood. To punish mankind’s inflated pride, this time God sent not deluge but division: “Go, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech” (Genesis 11:7). The citizens of Babel woke up mutually incomprehensible to one another. They scattered to the far reaches of the Earth to begin dysfunctional nations of their own.

The parable warns against hubris in general. More specifically, it guards against the particular megalomania homogeneity tends to spawn when humanity is of one language and one mind. I imagine a single bad actor with big dreams about that ancient Tower’s plumbing, and not a naysayer in sight. Humankind is terrifying when everyone agrees. Polyglotism is the gift that saved us from ourselves.

In retrospect, I think “water main” must have been a mistranslation. A “water main,” I have since learned, refers to the municipal supply—a collective resource, like the Nile or the ocean, that connects us even when we hate each other. The access point for any particular building is usually located in the basement. This makes it an unlikely culprit for a Flood originating on the top floor.

Pumping from the basement “water main” to the upper stories posed a challenge for early mass housing projects. The first developers relied on gravity, erecting the rooftop water towers you still see in cities like New York. By the 1970s, when our own housing block was constructed, engineers had figured out how to ratchet up the pressure to reach the highest floors, then lower it again through a series of valves. It is one of these pressure-regulating valves, I suspect, rather than the “water main,” that burst in our upstairs neighbor’s newfangled plumbing system sometime after midnight, raining many thousands of liters through the complex and flooding every single apartment below, especially ours. Gravity-powered plumbing was suddenly back in play. We woke up to a custom waterfall streaming down our bathroom walls.

At the time, we’d been in Geneva for a little over two years. When we first arrived, I spoke English and German; my husband, English, Bengali, Hindi, and a bit of Spanish. I had begun to learn French in earnest a few months before, when I’d found out I was pregnant. One of us would have to advocate for our child. I was up to the task. Then came the miscarriage, and I gave up. This complacency proved a liability in the aftermath of the Flood.

A lot of expats lack motivation to learn French in Geneva, and not only the Americans. You can get by pretty easily with the basics. Still, there’s less English than you’d think. At the tax office, or the immigration office, or over the phone with your healthcare provider, and especially in insurance disputes, people pretty reasonably prefer to speak French. Many don’t speak English at all. For the past two years, at the annual fête des voisins, my husband and I had stood in our building’s courtyard, nodding and smiling over glasses of wine, radiating what we hoped would be taken as nonverbal goodwill. There was linguistic friction, sure. But until we found ourselves trying to translate things like “water main,” the language barrier wasn’t really a barrier at all.

I’ve spent most of my adult life trying to make myself comprehensible. Even before we moved to Geneva—my husband works for one of those acronyms—when I was first teaching myself to write, I used to type up stories during lunch breaks at my Midtown office job. It was during this period that I came across the work of Viktor Shklovsky, the Russian Formalist. He wouldn’t have thought much, maybe, of my professional obligation to project and regularize the future based on what came before, which is more or less what statistics is. (I was a number-cruncher for insurance.) Art, Shklovsky argued, is meant to do precisely the opposite.

Shklovsky is most famous for his concept of “defamiliarization,” more commonly captured under the writer’s imperative to “make the familiar strange.” Human perception tends toward routine. It renders our experiences “habitual” and “automatic,” to the point where we stop noticing things at all. The job of literature, by contrast, is to make us see the disaster-zone to which we have grown accustomed as if “for the first time.” Shklovsky was a smart guy. He has since been validated by neuroscience: today we understand that the human brain not only filters out but furnishes known variables, the white noise of our lives. When we enter a room, we supply what we already expect to see, rather than deducing dimensions and contents from scratch. We fill our prescriptions and fifteen minutes later ask, “Did I take my pill today?” We become quickly inured to the ribbons of paint peeling from the still damp walls. Leonardo da Vinci, by contrast, once wrote that a real painter, “by looking attentively at old and smeared walls,” can “see in them several compositions, landscapes, battles, figures in quick motion, strange countenances, and dresses, with an infinity of other objects.” If there were divine signs to be detected in our peeling living room, I missed them.

It is due to our tendency to project the familiar onto a world of strangeness that neuroscientist Anil Seth, professor of cognitive and computational neuroscience at the University of Sussex, argues that consciousness is less a form of “processing” external information than a “sustained hallucination” originating in the brain. The most energy-efficient form of perceiving life starts from within your cranium, rooted in biological processes designed to recognize what is already expected, and then projects outward, rather than the other way around. In other words, we do not take in the world “as it is,” whatever that may be, but stage passive best guesses based on prior experience. Encounters with the unfamiliar—or the defamiliarized—interrupt this hallucination. They bring us out of ourselves. A Russian Formalist like Shklovsky calls this encounter art. A moral philosopher, someone like Levinas, might call it an encounter with “the Other.”

The actual brain-rewiring required to become more attentive to our surroundings is related to my favorite definition of plot, which Shklovsky later derived from this same concept. If slowing down is a “general law of art,” then plot is a “retardant force.” It’s what prevents a story from ending too soon, or at the wrong time. It tricks us into lingering where a more efficient storyteller would hurry on. To see or experience things as if for the first time, in other words, takes time.

Consider for a moment the Tower of Babel not as an isolated narrative, but as one episode in a much longer, more literary plot—the epic (and, from the view of most major religions, unfinished) story of humanity’s attempt to reach heaven. From this point of view, God’s motivation for sowing linguistic division on Earth isn’t “punishment.” It is, rather, what is needed to slow the story down, to keep the plot from ending too early, before its full effect has been realized. After all, at the time Babel fell, the human race hadn’t even founded its many nations yet. Pentecost was still a long way off, buried in the Book of Acts. On that day, the Holy Spirit—the water main of Christendom—flowed through the Apostles, allowing them to speak every language at once. Fluency became an act of grace. I find it increasingly significant that this miracle, often interpreted as a “reversal” of or coda to the Babel curse, did not, in the end, collapse the world’s tongues into one.

If you really want to learn a language, I suggest entering a legal dispute. I now speak Flood French, learned through months of wading through the insurance claims, repairs, and negotiations a major deluge entails.

It was in line at the renters’ association, where we pay dues, that I had my own Pentecostal breakthrough. Our landlords had denied our request for a rent reduction. There were still confusing disagreements over who ought to pay for repairs. The morning I arrived, there were maybe forty of us crammed into folding chairs in the carpeted lobby, clutching copies of our leases and awaiting appointments with association lawyers. An underpaid staffer took the opportunity to solicit us for a survey. Could we anonymously provide our addresses, rents, and approximate square meterage for a collective database meant to support future appeals for rent decreases? This rationale reached me with the burst of clarity that usually accompanies a righteous suggestion, soon overwhelmed by the clarity of actual comprehension: I understand.

Our new place is on the train tracks. I am eight months pregnant. From the front room, you can watch the express line come in from Paris. (The child in me imagines my own child doing just this, her face pressed up against the glass.) There’s a pawn shop across the street, next to an anarchist bookstore. Voltaire’s former villa is just up the hill.

My Flood French has since expanded to cover negotiations with movers, pediatricians, the nurse who administered my prenatal iron transfusion, the midwife who taught my birthing class. (Oui à la douleur!) At the Bureau d’information petite enfance, reserving my daughter a spot in publicly subsidized daycare (crèche) in my waterlogged accent, I feel vulnerable on her behalf. What if I miss something? What if I don’t understand? What if, by the simple fact of being foreign, I harm her chances of gaining access to services, of fitting in? These are the kinds of questions that drive you to the language school. My classmates were notably all women, mostly mothers, and overwhelmingly refugees from Afghanistan, Kurdistan, Iran, and Iraq. An interloping New Zealander claimed an allergy to the sun and to Geneva’s water supply, in response to which she’d developed a rash and a rich grammar of complaints.

One day, the exhausted teacher (nationality: French), out of tricks, posed a lazy conversation starter: “What is one positive and one negative stereotype about your country?” We spoke around the obvious. We lacked the vocabulary. The teacher conflated someone’s pronunciation of touriste with terroriste. We took to sharing wedding photos instead.

The above are also the kinds of questions—am I equipped to raise my child here?—that generate the baseline paranoia that is any parent’s due. Though one hardly needs to be a parent to be paranoid. There was another game we played in language class that I’ll call, How Swiss is it? The projector flashed images of mountains, a cow with its bell, Heidi from the famous 1974 Japanese anime series, whose avatar—now quintessentially Swiss—welcomes you on inter-terminal trains in the Zurich airport. We discussed the Swissness of swimming, skiing, fondue, glacial lakes. Geneva, for its part, is perched on Lac Léman, from which the canton’s water supply is sourced. It is considered “Swiss” to swim in it all year round, even in the winter; I know at least one foreigner who, in an arctic attempt to assimilate, developed temporary nerve damage. What is one positive and one negative stereotype about your country?

The construction of such clichés, Shklovsky taught me, amounts to the absence of mystery. A quest for purity always does. It imposes a totalizing familiarity. Its logical conclusion is a purge. Where cliché succeeds, everything worth looking at will disappear. In such a world, there is no need for language or stories anymore. (Why write, if I’m already convinced that your sustained hallucination is just like mine?) It occurs to me there will always be people with ambitions to divert the water main. How laughable that anyone could still believe that they, and they alone, will be spared the Flood.

This essay is part of Strange Visions, our ongoing series on defamiliarization.