The Architecture of Transformative Experience

Luke Burgis, Ben Hunt, Jennifer Paxton, and Fr. Mark Roosien.

Introduction

The following is an edited transcript from Cluny Institute’s 2025 METANOIA conference, which brought together speakers from across disciplines to discuss the nature of conversion. The following conversation, The Architecture of Transformative Experience, explores change at its most fundamental levels, through the lenses of theology, history, narrative, and more.

Ben Hunt is the chief investment officer of Second Foundation Partners, and the author of Epsilon Theory. He has a Ph.D from Harvard University, was a tenured political science professor, and has co-founded three technology companies.

Jennifer Paxton is a professor of History at the Catholic University of America. She is the director of the University Honors program, and received her Ph.D from Harvard University.

Fr. Mark Roosien is a priest of the Orthodox Church in America, and a Lecturer in Liturgical Studies at Yale University. He is a translator, author, and the rector of Holy Ghost church in Bridgeport, CT.

Conversation

Luke Burgis: We hear about “vibe shifts” all the time: The Christian vibe shift in Silicon Valley, political shifts, cultural shifts. For this conversation, we want to get underneath the vibe shift. What are we really talking about? What should we be thinking about when we're thinking about substantial change?

Ben Hunt: Exploring change through story and technology has been the object of my desire for my entire life. It's what Alfred Hitchcock called the MacGuffin, which for me has always been trying to figure out the structure of unstructured data. And the structure of unstructured data is story.

I've explored the structure of unstructured data across different fields. In academia—political science, of all oxymorons—then in software companies, and more recently in markets and finance, which is all narrative and storytelling.

It wasn't Tolstoy who said this, but it's attributed to Tolstoy, that there are only two stories: A man goes on a journey, and a stranger comes to town. But the fact is that there are more than two stories. There are twelve.

There are twelve stories in any field that the human animal can hold in its head at once. In Hollywood, there are twelve scripts for rom-coms. There are twelve scripts for police procedurals. It's true in investing; there are twelve scripts for understanding U.S. retail sales.

These stories wax and wane in ourselves and in society.

In all of my work about the stories that are necessary for positive change—and this is true whether we're talking about politics, markets, or sports—having a story of safety is foundational for human change and development.

Jennifer Paxton: In the history of monasticism, there are also two stories: A man hears what the gospel says about selling all you have and giving it to the poor, and a group of people decides to live in common like the apostles. These two stories recur over and over in the history of the church. But every time they do, they manifest themselves differently. So every time people think they're going back to the original narrative, they're actually creating something new.

Luke gave us an essay to read before this conference: “Innovation and Repetition.” It's about the balance between changing and preserving; how every time you're doing something, you're doing both of those things and trying to balance the two. If you don't get that balance right, you won't have something that both preserves what’s valuable from the past and also creates something new that's appropriate to the moment.

That balance is what fascinates me.

Fr. Mark Roosien: When I was asked to present at this conference about metanoia, obviously my first thought went to religious conversion. Not necessarily in the sense of converting from one religion to another, but what does it mean to convert to God?

Theology is a way of seeing reality. It's a way of understanding reality that allows you to find God within reality, and to find yourself in the same world as God.

That process is a process of conversion. It's a process of coming to see yourself and God in the same world, and beginning to interact. And that involves the work of the imagination. It involves a creative faculty within the mind, and also within the community, to be able to see all of it as existing within a story, within a world.

You have information and data, and you have a knowing subject. You have a structure of mind. And the goal is to get these two things to come together. But where does that happen? In the imagination.

Ben: Our physical ability to perceive and process information is actually quite limited. The sensory inputs we have only make sense if we can put them into a story. Our autonomy of mind has always been under assault. Narrative is intentional.

I think the question is: What scripts are running through our head?

There has been an enormous change in the world—I think a negative change—that comes first and foremost through this little dopamine machine that all of us have here [lifts up smartphone]. As with most profound changes, it's not that somebody has done this to us. It's not 1984, where there's the screen you can't turn off. We willingly adopt it.

This machine is the last thing I look at when I go to bed. It's the first thing I look at when I wake up in the morning. Not my wife—my iPhone. How sad and pathetic is that?

What stories are we absorbing? Do we maintain critical distance from those stories? That's the mission.

Luke: In the gospels, John the Baptist says, “Repent, the kingdom of heaven is at hand.” And he actually says, “metanoia, the kingdom of heaven is at hand.” There's a call to change everything. But not everybody who heard it changed. How should we think about the role of agency in the process of change from a theological perspective?

Fr. Mark: Whenever you want to change, there has to be an element of desire. It’s paradoxical, because you're not exactly sure what you want to change into, or what new story you want to appropriate, but you have to know enough about it to desire it.

That's where the imagination comes in. There is a third-century theologian, Origen of Alexandria—a very speculative, mystical philosopher—and one of his great works is an incredible commentary on the Old Testament book, the Song of Songs. If you've read the Song of Songs, you know it's a very saucy book. Origen says that this book is not for everybody—it's only for the spiritually advanced, because if you read it without sufficient spiritual advancement, you're going to fall. You're going to be seduced by what's in the book. So he writes a commentary for the spiritually advanced, in which he describes the story of the bride and the groom as an allegory between the soul and God.

But what's interesting about Origen is that he actually breaks his own rule. He says only the spiritually advanced should read the Song of Songs, and yet he also wrote two short homilies on the Song of Songs, which were written for catechumens—people who are preparing to enter into the church. They're not even baptized Christians yet. So how is it that he has such a stern warning that you should not read this book until after you’ve reached a high level of spiritual maturity, yet he's also talking about it with these baby Christians? I think it has something to do with desire.

The spiritual masters are able to access an almost erotic experience of God through the text. They are given the role of the bride entering the bridal chamber, and everything that comes with that. But in the short homilies for the beginner, they don't get to play the role the bride. They get to embody the bride's friends who stand outside the house.

They get to peek in the window and see what's going on in there, but they're not allowed to enter. Origen says, You have to stay outside for now. You're not ready to enter into this grand story of God and the soul. Your job right now is to stand outside and imagine what it’s going to be like, to peer in through the window. He is basically trying to elicit a kind of desire from them through imagination.

When it comes to agency, the idea is to ignite within the learner, the beginner, a desire to keep going, and to realize that the story that they're going to be entering—the change that they're going to make—will be better than what they live in now.

It's going to be better than the phone. But you have to elicit desire to break free from the world that you live in currently, and that takes agency.

Luke: I describe my own process of conversion as a change of desire. My desires literally changed. There's something to be said about the role of mystagogy: A mystagogue is one who leads others into a mystery. And that's a very different thing than telling people answers, or teaching them facts.

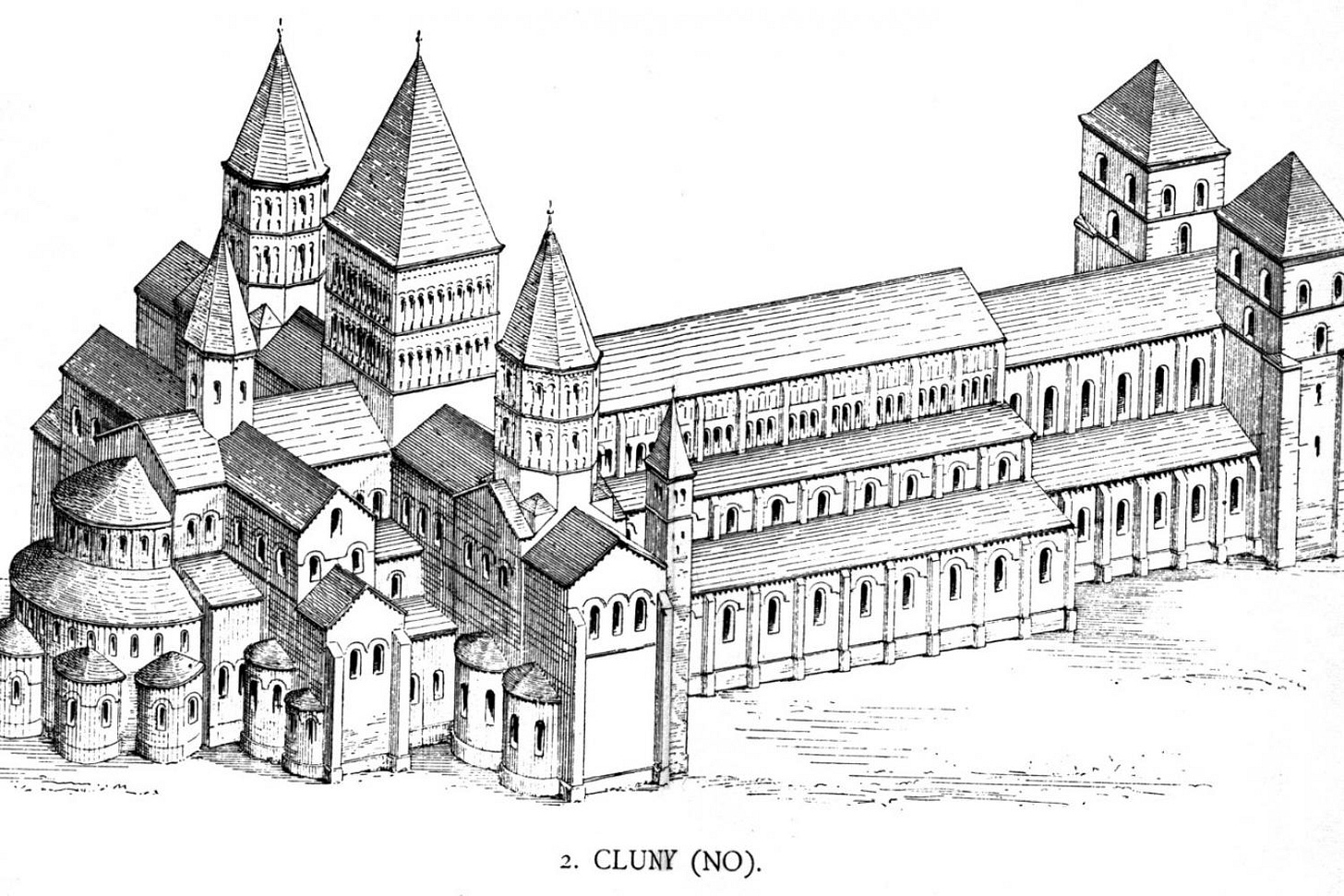

Jenny, as you and I were talking about this, you had mentioned that at the time of Cluny—which I'm obviously partial to—to convert or to change one's life basically meant to become a monk.

Jennifer: That's right. In the period of Cluny—the early 10th century—most of Europe was nominally Christian. We don't have a lot of insight into what people in rural areas, or lesser socioeconomic rungs, thought about religion. But the elite were at least nominally Christian, and some of them were profoundly Christian. So when they felt a call to deepen their experience of religion, most of the time it meant joining a monastic house.

An alternative, though, was for them to become monastic patrons. That was how you could have your cake and eat it too. You could sponsor the religious life, but you could stay in the secular world. And so monastic reform in the Middle Ages was that marriage between people in the secular world who would pay for it, and people who were willing to live it themselves.

That's what you get at Cluny. You get the partnership between the Duke of Aquitaine in southwestern France, and Odo of Cluny, who is one of the early saints of Cluny.

By the end of the 11th century, you have this Cluny project that stretches across Europe, encompassing hundreds of monasteries. And if you are donating to a Cluniac house, you know what you're going to get. You're going to get high quality intercessory prayer; all of those sins you're committing in the secular world are going to be prayed for, so that you're going to have a hope of salvation.

As a result, you get this wonderful monastic observance—people praying all over the place, and scholarship being done, and a culture being transformed. It all comes from that initial impulse at one place in southern France. And it founds the concept of the monastic order, which is the basis of so much of medieval religious life.

And then, you know, down to today.

Luke: Let's talk about the role of power and money when it comes to change.

Ben: We make sense of the world through stories. There’s a fractal element to that. We tell ourselves stories to get up in the morning. There’s a story element to how we understand politics. There’s a story element to understanding why we’re at this conference. But technology is now promoting narratives to us to a degree that it wasn’t in the past.

I'll point out two really non-cyclical changes. The first is in our system of media. We've moved towards the 24/7 presentation of narratives: Not entertainment, but scripts for how to understand the political and economic world. It's 24/7 news across all sorts of different political arenas. Similarly in the business world, there's not enough content for 24/7 news. I call it fiat news, like fiat money—it's made up news.

And there is agency behind that. There is AB testing on all of that—everything about our consumption, attention, votes, all of that. There are trillions of dollars spent behind the presentation of these stories.

The hardest thing in the world is to maintain critical distance. There's one simple thing you can do. You know, try this one simple trick, right? Ask yourself: Why am I reading this now? Why is this being presented to me now?

Fr Mark: When it comes to the question of money and narrative, I think about St. John Chrysostom, from the fourth century. He became a very powerful bishop of Constantinople, which was the major city of the Roman Empire at the time, because Rome was falling. He was very savvy about getting influential people to do what he wanted.

Some of what he wanted to do was build hospitals. The birth of the hospital in the Western world happens at this time. St John built these houses of hospitality, institutions for caring for the poor. His entire pastoral agenda for the city of Constantinople was to change it from being a late Roman metropolis whose story was focused on things like status, legacy, nobility; where noble familial lines were supposed to continue their legacy from generation to generation.

St. John Chrysostom basically says: None of that matters. What really matters is something quite different. The most important person in the room, he says, is not the person who's on stage. It's not the person who's sponsoring the event. It is the poor person, because the poor person is Christ. That's the narrative that he's trying to tell. He's trying to say that that's actually the truth of reality: The poor person is much more God-like than anybody here with wealth and status.

It's very realpolitik at times. He's leveraging his authority to pressure wealthy people to put their money into the narrative that he was telling—which was ultimately going to undermine their way of life.

Luke: Do we have to accept the notion that change must pass through the elites? Should we think differently about that question?

Fr. Mark: A lot of St. John Chrysostom’s sermons are preached to the elite because you didn't often have the poorest of the poor coming to church every Sunday—they're out surviving. What you have is people who are relatively elite, who can have some agency and power in the world. One of the reasons that John was so popular—and the reason he got the epithet Chrysostom, which means the golden mouth or the golden tongue—was because he had an incredible command of ancient Greco-Roman rhetoric. He was able to speak the language of the elite that delighted them—they would be clapping during his sermons. He'd be like, Stop clapping. It's not a show. He recognized that it was important to go around the elite, which he often did behind the scenes.

Pope Francis also did a lot of things behind the scenes that he didn't do in public. One of the things that I was most inspired by in the last months of his life was that he would FaceTime with a Catholic parish in Palestine to ask just how they were doing.

Jennifer: The word agency is related to the word agenda. Having an agenda literally means to have a to-do list. But we have to think about what's on that to-do list, and what is that person's goal? Why are they telling the story that they're telling, in the way that they're telling it? The humanities are important, because this is where we teach people how to interpret stories.

Fiction has an agenda. Fact has an agenda. Right now, we are in a period where we seem to be very divided. You watch MSNBC, or Fox News, and you wonder if you're on the same planet as other people. But there was a period from about the early 16th century down into the 19th century when everybody in Europe had an agenda too. It was either Protestant or Catholic, and everything was written through that lens.

There's a moment in the Enlightenment where people try to break out of that. But confessional history was the mode of historical writing that most people engaged in: As in, you belong to the Protestant confession or the Catholic confession.

That disappeared in the 19th century and hasn't really come back. We are in a moment that is a little bit similar, I think, in terms of how politics and culture are being written about.

But it will not always be like that.

Ben: I'm not optimistic. The reason I'm not optimistic is that there used to be a buffer, a distance between the people and the elite. Today, that buffer is gone. And it's gone because of what we carry in our pockets. It's a disaster. It’s an impingement on our autonomy of mind, when our betters shake their finger at us and tell us this is how to think.

Luke: Is there a question of our ability to perceive or sense reality? Are people losing their BS detectors or something? You used to be able to look somebody in the eye and know if that person is lying. Now, when everything is mediated to us through technology, it seems like that task is becoming a lot more difficult. How do we know if change is real? People can claim anything they want about the change they're going to make, or the change they've undergone. How might we develop the kind of perception to be able to see?

Fr. Mark: One danger of the imagination is the ability construct your own world. You just make stuff up, or build it by the narratives that come into your phone. And it's increasingly difficult to speak to people in another world.

But what real change demands is for you to have encounters that break apart the imaginary world that you've constructed, and force you to reappropriate something new. I think the best way that that happens is the face-to-face encounter with another person, especially someone who's different from you.

I come back to the French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, who talks about the face of the other as that which breaks into my world and demands something of me. A genuine encounter with another person places me in a state of humility. I need to acknowledge that they are in some sense above me, and I need to adjust my world and see its limitations. So the more we can get those kinds of encounters—which are becoming fewer and fewer, because we're much more satisfied to stay within the worlds [we create or] that have been created for us—the better.

Audience: Does agency or a desire to change necessarily proceed substantial change? The conversion of Paul suggests otherwise. Can one experience undesired transformation?

Luke: It took me a good ten years to even have any language to describe my own process of conversion. The best I've found comes from Rudolph Otto in his description of the holy. He describes the holy with a Latin phrase, the mysterium fascinans et tremendum.

It's a mystery that both fascinates and makes us tremble. There's a paradoxical combination of dread and something that's magnetically attractive, that almost seduces us. That's how he describes the holy: That which pulls us out of ourselves and draws us towards something.

Maybe that’s undesired change. It’s not forced on us, but at some point we have to step across the threshold of hope.

Audience: Can technology be a catalyst or facilitator of substantial change? Or is it simply a distraction and obstacle?

Luke: Technology is often so poorly defined. It seems like right now when we're asking about technology, we're almost asking about AI. I think there are questions that go far beyond AI that are very important, like praying with a prayer app: How does that change religious experience, for instance? One of the paradoxes of change is that it's really difficult to understand while you're actually going through it.

Fr. Mark: It's one thing to pray with the prayer app. It's another thing to pay for the prayer app.

Watch the full video of The Architecture of Transformative Experience here.

Happy this was released. I have a post that touches on this panel coming out in Cracks in PoMo next week.

There’s a great deal to appreciate here—especially the insistence that real change must involve both imagination and desire, not just data or doctrine. The dialogue makes a powerful case for the role of story, especially when it's embodied, face-to-face.

That said, I wonder whether we're in danger of over-relying on narrative as the master key. Not all distortions are story-shaped; sometimes it's the lack of concrete practice, material constraints, or institutional integrity that derails change. Story is essential—but it can also become another layer of performance unless rooted in something more than itself.