I spent much of my teenage years actively seeking out things that might depress me. I’d ask friends for recommendations, tell them my life was too easy and light. Bro… what do you know that will definitely depress me, something that will suck the air out of my mind? They told me to read Camus, Ligotti, Schopenhauer, Buddha, Houellebecq, etc., all outright hedonists as far as I could tell, empty basins waiting for pleasure to pour into them. It didn’t occur to anyone to tell me to read Hegel, possibly because all my friends were between fourteen and sixteen years old. If one or two of them had a vague sense of Hegel’s aura, extracted from Wikipedia or the eager tongue of some deranged relative, they knew him only as a tedious soothsayer of the irreducibly good, a standard-issue utopic-Teutonic conservative, who ate sausages and smiled in stiff benevolence at the cutely swelling bosom of his young, hot, aristocratic wife, who’d kindly agreed to adopt and raise Ludwig—fruit of Hegel’s liaison with his sexually powerful landlordess, Joanna—as her own.

In 2010, everything was still going fairly well in my life. I’d been unable, despite my best efforts, to break out of a general lightness and easiness that followed me around wherever I went, a sense that nothing was particularly true or untrue, nothing was determined, but nothing was not determined either; nothing was necessary, but nothing was not necessary either. Everything, I thought in my light-headed undergraduate egoism, existed on a spectrum, the worst you could do was move one or two inches in a given direction, slightly up or slightly down, slightly left or slightly right, but such adjustments were in the end so smarmily quantitative that overall it was better not to do anything except walk around with your headphones on, a bit of Handel, a bit of Bossa nova, your eyes seventy-two percent open to the extraordinary works of either God or nature, why should it matter which?

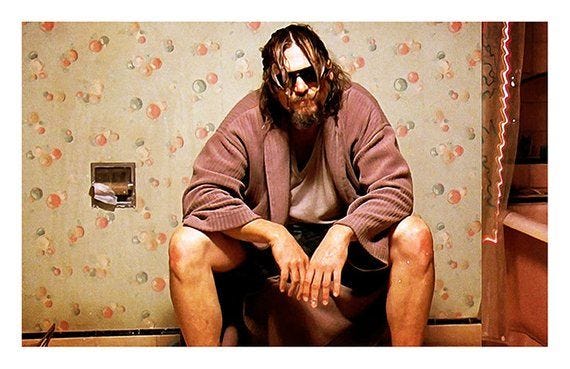

But at some point, wandering around various semi-European cities, distributing my time between (a) “looking at attractive people in the distance while listening to various songs composed between 1300 and 2012” and (b), “looking at attractive objects in the distance while listening to various songs composed between 1300 and 2012,” in short enjoying myself. I came across Hegel’s idea of Universal Reason and almost went insane1. A scene in the Coen Brothers’ The Big Lebowski demonstrates the mad power of this idea very well. The film’s long-haired protagonist is minding his business when suddenly several nihilists invade his apartment. He’s uncooperative, even courageous; he doesn’t seem to mind very much what they’re doing. Yes, he’s upset when the Asian nihilist cynically micturates on his rug, but he’s not thrown into confusion; he takes everything more or less as it comes, offering by way of resistance only a gently pleading counter-commentary (come on… no, don’t do that… not on the rug, man.)

Something of him, then, is beyond all this, beyond the reach of the nihilists’ insults and cheap threats. This is confirmed when the more Germanic of the two nihilists drags him to the bathroom and jams his head down the toilet. He pulls him up, says where’s the money Lebowski, puts him back, pulls him up again, says where’s the money Lebowski, puts him in, pulls him out, says where’s the [redacted] money, shithead? Perfectly ventriloquizing Universal Reason, “the dude” answers: it’s down there somewhere, let me take another look. Meaning: sure, but bro, why don’t you take another look, the human community from which you’ve pointlessly excluded yourself might be down there somewhere too, how do you know if you don’t look? You look like you’ve already looked everywhere else, if you don’t mind me saying. But if you’re not willing to look for it this time, then hey, I’ll do it, I’m that kind of guy.

Herein the secret of Hegel’s rhetoric and system both: he nutritionalizes your critique. You push his head down the toilet, but it turns out he was just about to look down that particular toilet anyway; actually, it’s pretty difficult to jam your own head down a toilet, the physics are difficult, I was hoping you might come by. Whatever you do, you’re included; exclude yourself, and it will turn out to have been a necessary step—probably the ‘key step’—in your journey towards inclusion. And this is perfectly generalizable; the frantic energy of a rebellious child, interpreted Hegelianly, is merely an advance paid on his inevitable inclusion, the stamp of its authenticity.

Kierkegaard considered this philosophy a joke, the joke being that while the system of inclusion was perfect, the architect had forgotten to include any doors2. But Kierkegaard could only think this because he was already dwelling somewhere else, namely in God (or thereabouts). He was correct to observe that Hegel’s system is doorless. But contemporary subjectivity is homeless—where could the system be built but on the ground where you already are? The absence of doors, which meant for Søren Aabye Kierkegaard that there was no way in, means for you that there is no way out. What for Kierkegaard was an ‘almost funny’ joke is for you an impenetrable tragedy. Moral: to diagnose unbelief, measure how quickly humor turns into pain.

But you have to read Hegel twice, as, after being depressed for some time (2010-2023) for ‘no reason,’ I did; the truth is down there somewhere but you have to take another look. The first time you fail, the second time you fail again, but differently, revealing the necessity of your first failure; from this, you can infer that your second failure was necessary too. It’s not that Hegel himself succeeded and is mocking you from the skies, but that he failed before you, and even more horribly; he’s mocking you from below, punching up, as they say. Hegel’s point, in other words, is not that you are included, but that no one is—not-being-included is the only thing you have in common with anyone. The universal is a blanket you stretch until a small slit, shaped like a mouth, opens up in the middle; out of this the confession of the redeemed particular pours.

Until I looked down this mouth-like gap in the center of thought, I interpreted every attempt at inclusion as a power move of the cruelest kind. As the youngest child of four, perhaps this was natural; to be born last is to be nothing but included; your parents, your brothers, your sisters, they all, by default, know the world better than you, they know, even, of a completely different world, closed to you at the very point of your entrance, and they will take their double epistemological advantage to the grave. The includer, I said to myself, in including the includee, asserts total ontological supremacy; the includer is no less distinct from the includee than the murderer is from the murdered. And at least the murderer has no chance to celebrate his crime, having killed the real witness; the includer, on the other hand, extends his ontological priority as far into the future as possible (oh yeah, feel free to come back any time… don’t forget, there’s always a place for you here). I’d managed to escape the trauma of inclusion by doing exactly that, forgetting about it, but after finding out about Universal Reason this was no longer an option for me. Nothing, Hegel says, is forgotten; forgetting is a preliminary step in a process not of cognition but of revenge. But revenge, luckily, is beautiful.

And realizing this is the first step in becoming a historical subject. Until then, I’d had seen history as an endless series of people, a world-historical expression of the same glutinous logic of inclusion which I hoped to defy or at least ignore in my personal life. Like people, historical events were constantly being added onto each other, for no reason other than to increase their overall gravitational pull. And so to read history, I thought, was only to smear my bad conscience on its surface, which it would of course “welcome”—come back any time, history seemed to say, there’s always room for you here. But reading Hegel for the second time, it instead came back to me; the Spanish Armada, which hadn’t even seemed real enough to be fake, Hiroshima, Christopher Columbus, all of this actually happened, and the reason it happened is that it didn’t entirely happen, it wasn’t able to squeeze the fruit of itself to the last drop. And how else could I ever explain how, when my uncle died at the end of that year, I was able to climb down the ladder of the negative all the way back to the final solitary eyelash of Jesus Christ?

For Hegel, Universal Reason is the idea that reality is structured by a self-developing logic that incorporates every contradiction into its own unfolding.

Hegel’s system explained everything, but didn’t tell you how to actually enter it as an individual subject—it indicated no path for personal decision, or faith.

I've never been knocked over by an eyelash before. Bravo.

Thank you for this article. I am currently writing the last paper of my undergrad. Going through my notes of the past three years, I definitely understand what you mean by « lightheaded undergrad egoism ». My notes are so full of arrogant commentary about solipsism. Strange era of my life. Definitely egoist in its nature.

You write very well. There is an attitude to your writing, a cadence, that feels almost jazz-like